Black History…

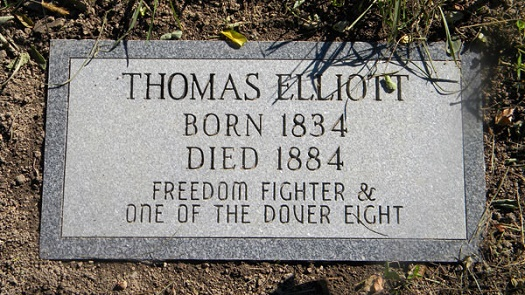

In March 1857, eight slaves from Dorchester County, Maryland, escaped following a route provided by Harriet Tubman, who also previously escaped from Dorchester County.

Tubman had told the fugitives to contact Thomas Otwell, a free black man and underground railroad conductor in Dover, Delaware. Unfortunately, instead of guiding them North to the next step of the railroad, Otwell led them to the Dover jail in expectation of collecting a $3,000 reward. However, despite the betrayal, the “Dover Eight” were able to escape the jail. All of them eventually made their way to freedom.

The slaves were discovered when a man approached Sheriff Green with the information about eight runaway slaves. The man arranged to have the slaves with him in Dover that night.

At about 4 o’clock on a Tuesday morning, the man along with the slaves appeared at the jail. While the sheriff was getting dressed, they all entered the jail and went upstairs. The eight slaves found an open room. The sheriff, knowing the group was upstairs, headed up there to dead bolt the room and seize them.

However, the sheriff found them in the entry way. He turned around and went back to retrieve his revolver, but the slaves followed him down to his room. The slaves entered the room where the sheriff’s wife and children were sleeping before he could seize his revolver.

One of the slaves reportedly became suspicious of the sheriff. The law enforcement officer quickly seized the man and, while in a struggle, the other slaves burst through a window and escaped. They made a fire scatter across the floor, which resulted in awakening the sheriff’s family. The sheriff released the slave for a split second, which allowed him to escape as well.

POSTED BY JAE JONES

Six of the eight slaves were later tracked down to a house in Camden, but the officers could not enter the home because they did not have a proper warrant. Later, the six men were moved through the country by the forest woods, which was later known as the “underground railroad.” The other two escaped slaves were seen heading north right after they escaped.

source:

http://aasc.oupexplore.com/undergroundrailroad/#!/event/slave-escape-dover

You must be logged in to post a comment.