Never forget …

Many Americans worried that citizens of Japanese ancestry would act as spies or saboteurs for the Japanese government. Fear — not evidence — drove t he U.S. to place over 127,000 Japanese-Americans in concentration camps for the duration of WWII.War II. Their crime? Being of Japanese ancestry.

he U.S. to place over 127,000 Japanese-Americans in concentration camps for the duration of WWII.War II. Their crime? Being of Japanese ancestry.

Despite the lack of any concrete evidence, Japanese Americans were suspected of remaining loyal to their ancestral land. Anti-Japanese paranoia increased because of a large Japanese presence on the West Coast. In the event of a Japanese invasion of the American mainland, Japanese Americans were feared as a security risk.

Succumbing to bad advice and popular opinion, President Roosevelt signed an executive order in February 1942 ordering the relocation of all Americans of Japanese ancestry to concentration camps in the interior of the United States.

Evacuation orders were posted in Japanese-American communities giving instructions on how to comply with the executive order. Many families sold their homes, their stores, and most of their assets. They could not be certain their homes and livelihoods would still be there upon their return. Because of the mad rush to sell, properties and inventories were often sold at a fraction of their true value.  After being forced from their communities, Japanese families made these military-style barracks their homes.

After being forced from their communities, Japanese families made these military-style barracks their homes.

Until the camps were completed, many of the evacuees were held in temporary centers, such as stables at local racetracks. Almost two-thirds of the interns were Nisei, or Japanese Americans born in the United States. It made no difference that many had never even been to Japan. Even Japanese-American veterans of World War I were forced to leave their homes.

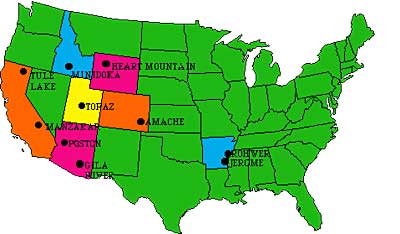

Most of the ten relocation camps were built in arid and semi-arid areas where life would have been harsh under even ideal conditions.orced to leave their homes.

Ten camps were finally completed in remote areas of seven western states. Housing was spartan, consisting mainly of tarpaper barracks. Families dined together at communal mess halls, and children were expected to attend school. Adults had the option of working for a salary of $5 per day. The United States government hoped that the interns could make the camps self-sufficient by farming to produce food. But cultivation on arid soil was quite a challenge.

Evacuees elected representatives to meet with government officials to air grievances, often to little avail. Recreational activities were organized to pass the time. Some of the interns actually volunteered to fight in one of two all-Nisei army regiments and went on to distinguish themselves in battle.

Fred Korematsu challenged the legality of Executive Order 9066 but the Supreme Court ruled the action was justified as a wartime necessity. It was not until 1988 that the U.S. government attempted to apologize to those who had been interned.

Fred Korematsu challenged the legality of Executive Order 9066 but the Supreme Court ruled the action was justified as a wartime necessity. It was not until 1988 that the U.S. government attempted to apologize to those who had been interned.

Fred Korematsu decided to test the government relocation action in the courts. He found little sympathy there. In Korematsu vs. the United States, the Supreme Court justified the executive order as a wartime necessity. When the order was repealed, many found they could not return to their hometowns. Hostility against Japanese Americans remained high across the West Coast into the postwar years as many villages displayed signs demanding that the evacuees never return. As a result, the interns scattered across the country.

In 1988, Congress attempted to apologize for the action by awarding each surviving intern $20,000. While the American concentration camps never reached the levels of Nazi death camps as far as atrocities are concerned, they remain a dark mark on the nation’s record of respecting civil liberties and cultural differences.

ushistory.org

You must be logged in to post a comment.