June 4, 1919

Throughout its history the Senate has cast many crucial votes that have broken a deadlock to bring about legislative success. On June 4, 1919, the Senate cast one such vote when it approved the Woman Suffrage Amendment, clearing the way for state ratification of the Nineteenth Amendment. That success did not come easily. It took years of activism by suffragists, and some brilliant maneuvering by one particular female lobbyist, to gain Senate support for a woman’s right to vote.

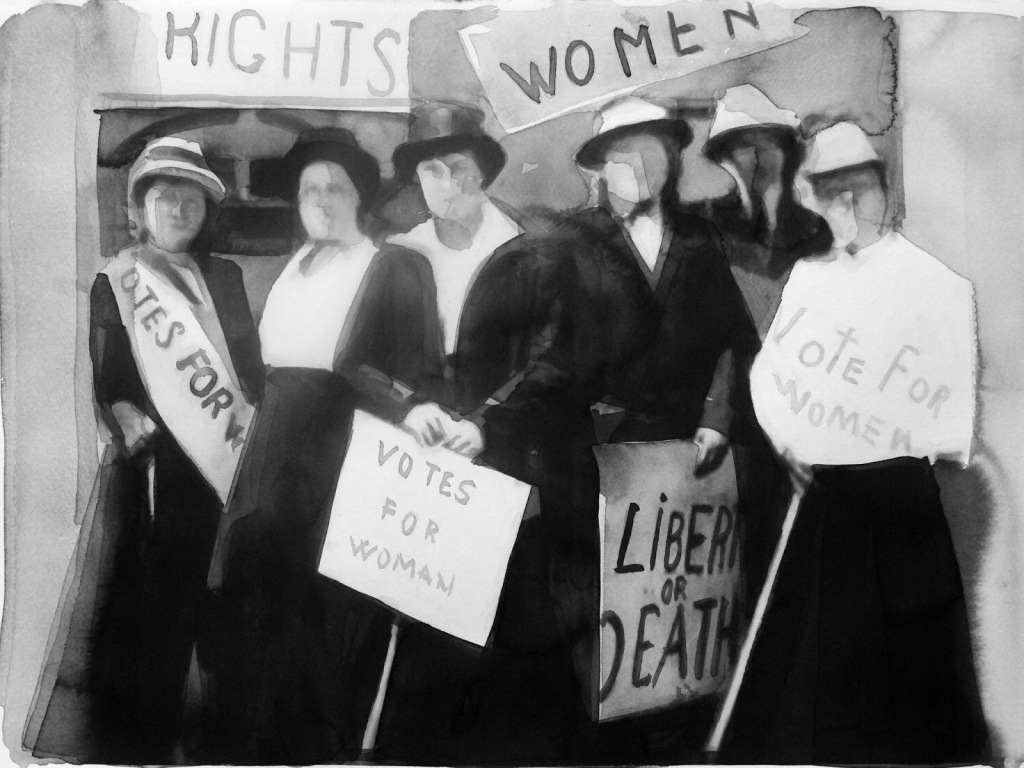

One of the suffragists’ first campaigns in the Senate came in 1913. The so-called “Siege of the Senate” brought to Washington hundreds of female activists who arrived in a parade of automobiles and carried petitions for voting rights signed by more than 200,000 women. “We want action now,” chanted the suffragists as they marched into the Capitol. Opponents called the siege a cheap advertising trick, but as the women filled halls and committee rooms, armed with banners, picket signs, and lengthy petitions, senators paid attention.

Senators who supported suffrage rights quickly took the floor and introduced petitions for women of their home states. Giving women the vote, Reed Smoot of Utah observed reassuringly, “has made no daughter less beautiful, no wife less devoted, no mother less inspiring.” Senators opposed to female suffrage, feeling pressure from the lady lobbyists, also participated. “I wish to say that I am opposed to the passage of the amendment,” explained John Thornton of Louisiana, before obediently submitting a petition. Joseph Johnston of Alabama explained that his petition came “at the request of one lady,” then left to speculation the identity of that singular suffragist. “Whatever may be my personal view on this matter,” James Martine of New Jersey confessed, “I would be a veritable coward [should] I not present this petition.”

As years passed, and the Senate remained a barrier to reform, the activists intensified their efforts. Leading the way was a savvy operator named Maud Younger. Although Younger employed a variety of tactics, her most effective strategy was the use of a “congressional card index,” a voluminous collection of index cards on which she recorded every detail, public and private, that she learned about each member of Congress. No detail was overlooked. If the cards noted that a senator always arrived at his office at 7:30 a.m., Younger had a suffragist there at 7:29. If a senator smoked cigars, she sought support among his state’s cigar-makers, or his lodge members, or the family doctor, or anyone else who might influence his vote. She found it especially useful to collect information about the senators’ mothers. Some men, she explained, “listen to their mothers more than to their wives.” By 1919 the tide of Senate opinion was shifting, prompting Maud Younger to boast: “Twenty-two senators have changed their position since I came to Washington.”

On June 4, 1919, 37 Republican senators joined 19 Democrats to pass the amendment. In quick succession, states then ratified the amendment, with Tennessee becoming the necessary 36th state to approve on August 18, 1920. Once again, a Senate vote had provided the crucial bridge to success. In reviewing the tactics that helped bring about that successful Senate vote, the New York Times paid special tribute to Maud Younger and her sister lobbyists. “In the hands of determined women,” concluded the Times, “a full card index is even mightier than pen or sword.”

You must be logged in to post a comment.