This commentary is part of The Appeal’s collection of opinion and analysis.

Story by Jay Willis

If you’ve ever seen a police procedural on TV, you are likely aware that officers are supposed to tell you about certain rights when you’re arrested. “You have the right to remain silent. Anything you say can be used against you in a court of law,” a common version begins. “You have the right to an attorney. If you cannot afford an attorney, one will be provided to you before questioning takes place.”

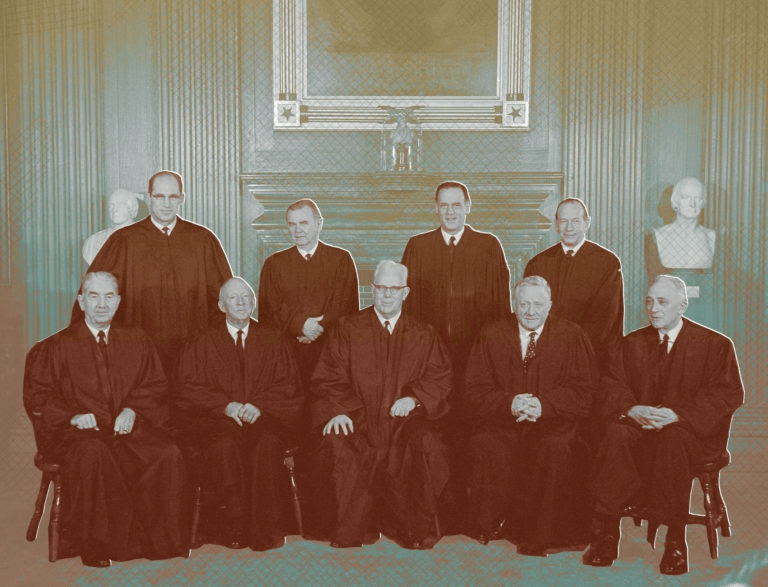

This disclaimer, known as the Miranda warning, is the product of a landmark 1966 U.S. Supreme Court decision, Miranda v. Arizona. It is meant to protect Americans from submitting to the police simply because they think, under the circumstances, that they have no other choice. If police don’t first recite it to people who are in custody, anything they say during subsequent interrogations cannot be used against them in court.

In theory, at least. In the five decades since creating this safeguard, the Court has been consistently chipping away at it, carving out generous exceptions and crafting new rules that limit its real-world impact. Together, these carve-outs preserve the Miranda warning in form, while ensuring that it does as little as possible to keep people—especially members of marginalized

Source: theappeal.org for the complete article

You must be logged in to post a comment.