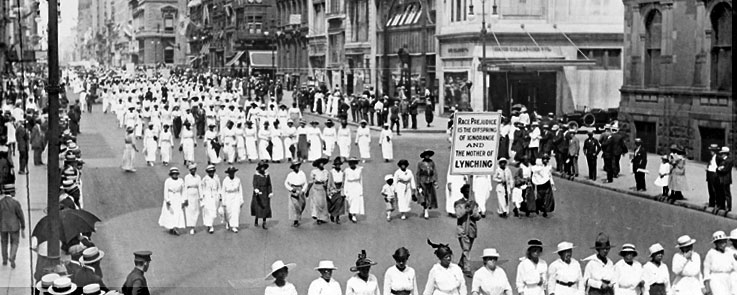

Jul 27, 2020 The July 28, 1917 Silent Protest Parade on Fifth Avenue in New York City, was one of the first major mass demonstrations by African Americans. Conceived by James Weldon Johnson and organized by the NAACP with church and community leaders, the protest parade united an estimated 10,000 African Americans who marched down Fifth Avenue, gathering at 55th–59th Streets and proceeding to Madison Square, silently carrying banners condemning racist violence and racial discrimination. More info: https://beinecke.library.yale.edu/191…

Daily Archives: 07/28/2025

1996 Kennewick Man, the remains of a pre~historic man, is discovered near Kennewick, Washington.

Two men at a Washington state park stumble on a skull, part of a skeleton later found to be over 9,000 years old—one of the oldest in N. America. “Kennewick Man” is reburied 21 years later, in Native American rites.

It is one of the most complete ancient skeletons ever found.

Age: 8.9k – 9k years BP

Common name: Kennewick Man

Place discovered: Columbia Park in Kennewick, Washington

Species: Homo sapiens

Language: Nahuatl

Source: history.com , internet, ancient-origins.net

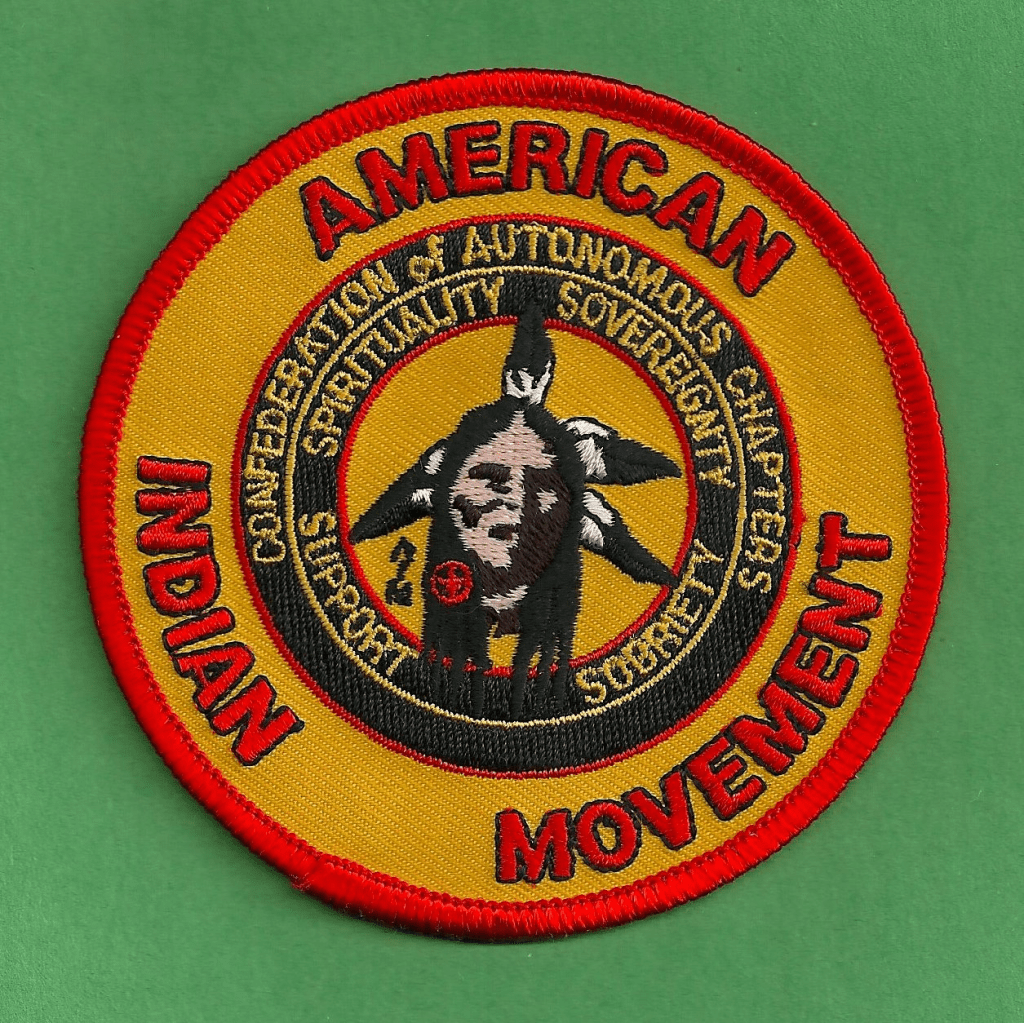

1968 – American Indian Movement(AIM) is founded

On July 28, 1968, several hundred Native Americans in Minneapolis, Minnesota attend a meeting, organized by community activists George Mitchell, Dennis Banks and Clyde Bellecourt, to discuss issues facing their local Indigenous community. This event marks the start of the American Indian Movement, or AIM, a primary proponent of the Red Power movement. Inspired by the gains of the Black civil rights movement, AIM sought to address the extreme suffering of Indigenous people and create a path for self-determination and empowerment.

For centuries, Native Americans had suffered relentless efforts by the U.S. government to make them disappear—through massacres, forced removal from their homelands and forced cultural assimilation. For attendees of the first AIM meeting, the most recent incarnation of those harmful policies was the 1956 passage of the Indian Relocation Act. Part of the government’s effort to end its support for tribal nations and reclaim reservation lands, the act created a program of vocational training for Native Americans, incentivizing them to leave their reservations and assimilate into urban areas. Most who made the move struggled mightily with the compounded realities of low-wage labor, poor housing, diminished support networks and systemic discrimination.

Source: history.com for the complete article

Bonus Marchers evicted by U.S. Army

On July 28, President Herbert Hoover ordered the army to evict them forcibly. General MacArthur’s men set their camps on fire, and the veterans were driven from the city. Hoover, increasingly regarded as insensitive to the needs of the nation’s many poor, was much criticized by the public and press for the severity of his response.

Source: history.com

NAACP Silent Protest Parade, New York City 7/28/1917

The National Association of the Advancement of Colored People’s (NAACP) Silent Protest Parade, also known as the Silent March, was held in New York City on Saturday, July 28, 1917, on 5th Avenue. This parade came about because the violence acted upon African Americans, including the race riots, lynching, and outages in Texas, Tennessee, Illinois, and other states.

One incident in particular, the East St. Louis Race Riot, also called the East St. Louis Massacre, was a major catalyst of the silent parade. This horrific event drove close to six thousand blacks from their own burning homes and left several hundred dead.

James Weldon Johnson, the second vice president of the NAACP, brought together other civil rights leaders who gathered at St. Phillips Church in New York to plan protest strategies. None of the group wanted a mass protest, yet all agreed that a silent protest through the streets of the city could spark the idea of racial reform and an end to the violence. Johnson remembered the idea of a silent protest from A NAACP Conference in 1916 when Oswald Garrison Villard suggested it. All the organizations agreed that this parade needed to be comprised of the black citizens, rather than a racially-mixed gathering. They argued that as the principal victims of the violence, African Americans had a special responsibility to participate in this, the first major public protest of racial violence in U.S. history.

The parade went south down 5th Avenue, moved to 57th Street and then to Madison Square. It brought out nearly ten thousand black women, men, and children, who all marched in silence. Johnson urged that the only sound to be heard would be the “the sound of muffled drums.” Children, dressed in white, led the protest, followed by women behind, also dressed in white. Men followed at the rear, dressed in dark suits.

The marchers carried banners and posters stating their reasons for the march. Both participants and onlookers remarked that this protest was unlike any other seen in the city and the nation. There were no chants, no songs, just silence. As those participating in the parade continued down the streets of New York, black Boy Scouts handed out flyers to those watching that described the NAACP’s struggle against segregation, lynching, and discrimination, as well as other forms of racist oppression.

James Weldon Johnson wrote in his 1938 autobiography, Along This Way, that “the streets of New York have witnessed many strange sites, but I judge, never one stranger than this; among the watchers were those with tears in their eyes.”

Sources:

Jessie Carney Smith, Linda T. Wynn, Freedom Facts and Firsts: 400 Years of the African American Civil Rights Experience (Visible Ink Press, 2009); James Weldon Johnson, Along This Way: The Autobiography of James Weldon Johnson (New York: Penguin Classics, 2008); James Barron, “A History of Making Protest Messages Heard, Silently,” The New York Times (June 2012); “Snippet From History #2: The Negro Silent Protest of 1917,” http://www.usprisonculture.com/blog/2013/02/28/snippet-from-history-2-the-negro-silent-protest-of-1917/; “The Negro Silent Protest Parade,”

https://nationalhumanitiescenter.org/pds/maai2/forward/text4/silentprotest.pdf.

You must be logged in to post a comment.