The burned interior of the station wagon that was discovered following the disappearance of activists Michael Schwerner, James Chaney, and Andrew Goodman.

The KKK was in a murderous mood. It was June 1964—the start of “Freedom Summer,” a massive three-month initiative to register southern blacks to vote and a direct response to the Klan’s own campaign of fear and intimidation.

The Klan in Mississippi, in particular, was after a 24-year-old New Yorker named Michael Schwerner. He’d been especially active in organizing local boycotts of biased businesses and helping with voter registration. On June 16, acting on a tip, a mob of armed KKK members descended on a local church meeting looking for him. Schwerner wasn’t there, so they torched the church and beat the churchgoers.

|

An FBI poster seeks the missing workers.

|

The Klan missed its target, but the trap was set: on June 20, Schwerner and two fellow volunteers—James Chaney and Andrew Goodman—headed south to investigate the fire. The next afternoon, they interviewed several witnesses and went to meet with fellow activists. The events that followed, outlined here, would stun the nation.

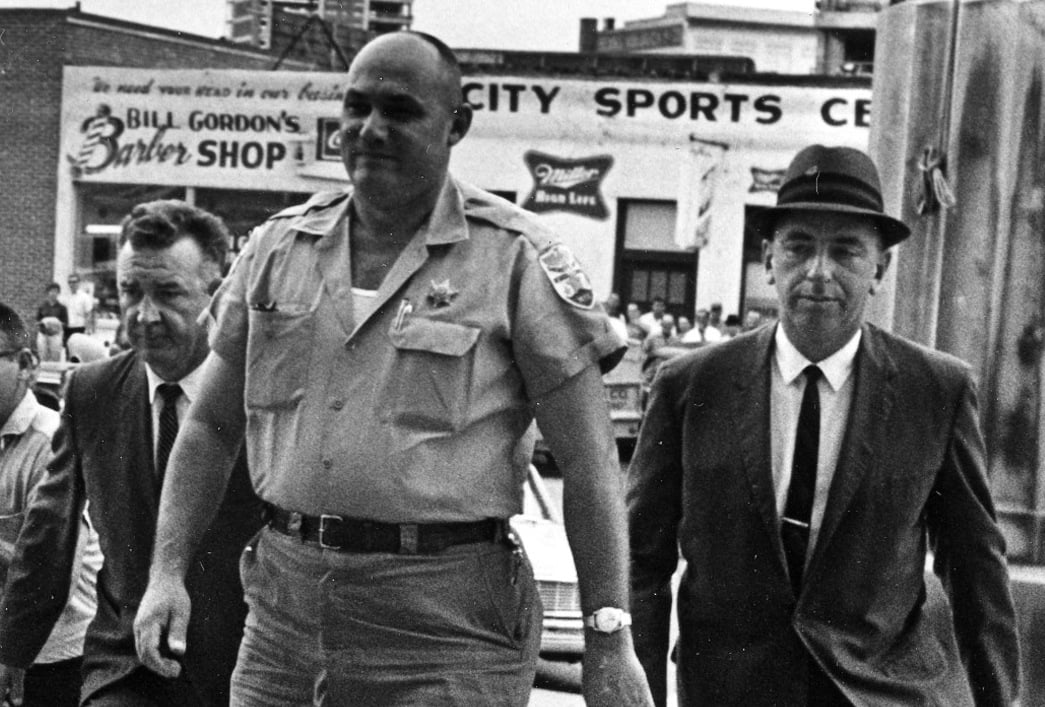

5 p.m. , Sunday, June 21: After driving into Philadelphia, Mississippi, the three civil rights workers were arrested by a Neshoba County Deputy Sheriff named Cecil Price, allegedly for speeding.

Circa 10:30 p.m., June 21: Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner were released and drove off in the direction of Meridian in a blue station wagon. By preordained plan, KKK members followed. The activists were never heard from again.

Early morning, June 22: Notified of the disappearance, the Department of Justice requested our involvement; a few hours later, Attorney General Robert Kennedy asked us to lead the case. By late morning, we’d blanketed the area with agents, who began intensive interviews.

Late afternoon, June 23: Intelligence developed by our agents led them to the remains of the burnt-out station wagon, shown above. No bodies were found; the worst was feared. The charred station wagon led us to name the case “MIBURN,” for Mississippi Burning.

June 24 to August 3. We launched a massive search for the young men—aided by the National Guard—through back roads, swamps, and hollows. At the same time, we were putting pressure on known members and developing informants who could infiltrate the Klan. At the request of President Lyndon Johnson, we also opened a new field office in Jackson, Mississippi. In time, we’d developed a comprehensive analysis of the local KKK and its role in the disappearance.

August 4. Acting on an informant tip, we exhumed all three bodies 14 feet below an earthen dam on a local farm.

December 4. More than a dozen suspects, including Deputy Price and his boss Sheriff Rainey, were indicted and arrested.

October 20, 1967. Following years of court battles, seven of the 18 defendants were found guilty—including Deputy Sheriff Price—but none on murder charges. One major conspirator, Edgar Ray Killen, went free after a lone juror couldn’t bring herself to convict a Baptist preacher.

1754 – Kings College opened in New York City. It was renamed Columbia College 30 years later.

1754 – Kings College opened in New York City. It was renamed Columbia College 30 years later.

You must be logged in to post a comment.