supremecourt.gov

(1) Did you know: It was actually on July 2, 1776, that America gained its independence. So why do we celebrate on July 4?

(1) Did you know: It was actually on July 2, 1776, that America gained its independence. So why do we celebrate on July 4?

Keep clicking to find out from Kenneth C. Davis, author of the “Don’t Know Much About” book series.

(5) John Adams and Thomas Jefferson both died on July 4, 1826. Davis explained, “That may be the most extraordinary coincidence in all of history. On the 50th anniversary of the adoption of the declaration…the two giants of the declaration both died. … Jefferson died first. Adams was alive, of course, in Massachusetts. He didn’t know that Jefferson had died but said, famously, perhaps apocryphally, that ‘Jefferson still lives.’ And people took that to mean his words will live forever.”

(6) The Liberty had nothing to do with July 4th. It wasn’t called the “Liberty Bell” until the 1830s and that’s also when it got its famous crack.

(7) Only two men signed the Declaration of Independence on July 4th, 1776 — John Hancock (not the big signature!) and Charles Thompson, secretary of the Congress.

(8) Jefferson’s original draft was lost and the one eventually signed is the “engrossed” document and is kept at the National Archives.

(9) The printed version of the Declaration was called the Dunlap Broadside – 200 were made but only 27 are accounted for. One of these was found on the back of the picture frame at a tag sale and sold at auction for $8.14 million to television producer Norman Lear. It now travels the country to be displayed to the public.

Resource: cbsnews.com

by Jenny Ashcraft

In February 1839, slave hunters abducted a group of Africans from Sierra Leone and shipped them to Havana, Cuba to be sold as slaves. Their kidnappings violated all treaties then in existence. When they arrived in Cuba, two Spanish plantation owners, Pedro Montes and Jose Ruiz, purchased 53 slaves to work their Caribbean plantation. They loaded the slaves aboard the Cuban schooner Amistad. On July 1, while sailing through the Caribbean, the captured slaves organized a mutiny. One of the slaves, Sengbe Pieh (also known as Joseph Cinque), freed himself and loosed others. They killed the captain and the ship’s cook, seized the ship, and ordered Montes and Ruiz to sail to Africa. Early in the morning of July 2, in the midst of a storm, the enslaved people rose up against their captors and, using sugar-cane knives found in the hold, killed the captain of the vessel and a crewmember. Two other crewmembers were either thrown overboard or escaped, and Jose Ruiz and Pedro Montes, the two Cubans who had purchased the enslaved people, were captured. Cinque ordered the Cubans to sail the Amistad east back to Africa. During the day, Ruiz and Montes complied, but at night they would turn the vessel in a northerly direction, toward U.S. waters. After almost nearly two difficult months at sea, during which time more than a dozen Africans perished, what became known as the “black schooner” was first spotted by American vessels.

Under the guise of heading towards Africa, Montes and Ruiz sailed the ship north instead. The Amistad zigzagged up the east coast for nearly two months.

On August 26, 1839, it dropped anchor off the tip of Long Island and a few of the men went ashore for fresh water. Soon, the US Navy brig Washington sailed into view. Thomas R. Gedney, commanding officer of the Washington, assumed those on board were pirates. He ordered his men to disarm the Africans and capture everyone including those who had gone ashore for water. They were all transported to Connecticut where officials freed the Spaniards but charged the Africans with murder upon the high seas.

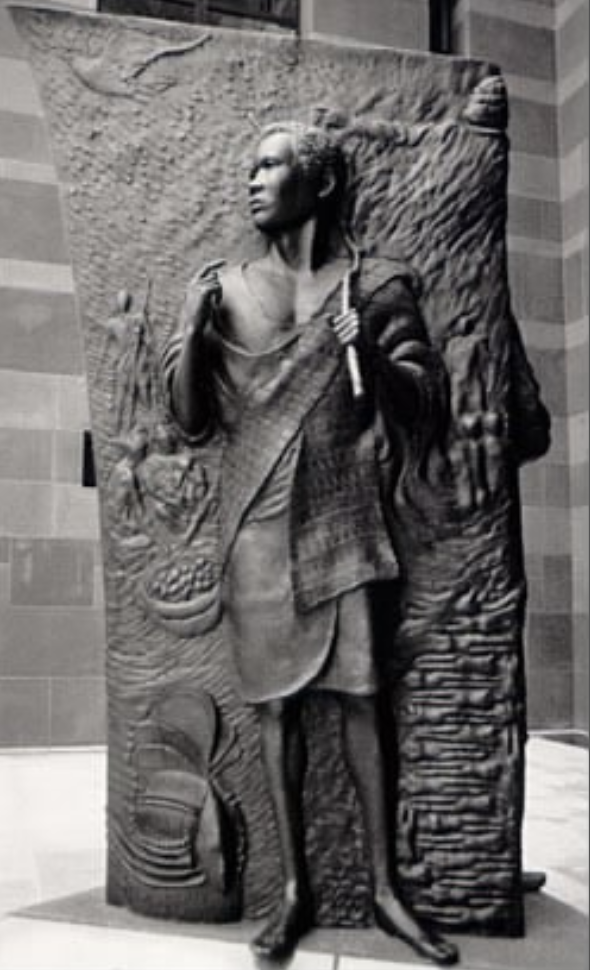

Amistad Memorial

New Haven, Connecticut

The murder charges were eventually dismissed, but the Africans remained imprisoned and their case sent to Federal District Court in Connecticut. The plant ation owners, the government of Spain, and Gedney all claimed some sort of compensation. The plantation owners wanted their slaves back, the Spanish government wanted the slaves returned to Cuba where they would likely be put to death, and Thomas Gedney felt he was entitled to compensation under maritime law that allowed salvage rights when saving a ship or its cargo from impending loss.

ation owners, the government of Spain, and Gedney all claimed some sort of compensation. The plantation owners wanted their slaves back, the Spanish government wanted the slaves returned to Cuba where they would likely be put to death, and Thomas Gedney felt he was entitled to compensation under maritime law that allowed salvage rights when saving a ship or its cargo from impending loss.

The district court ruled that the case fell within Federal jurisdiction. The ruling was appealed, and the case sent to the Supreme Court. Former president John Quincy Adams argued on behalf of the Africans. He said they were innocent because international laws found the slave trade was illegal. Thus, anyone who escaped should be considered free under American law.

The Supreme Court ruled in favor of the Africans and ordered their immediate release. Abolitionists who had supported their cause raised funds to return them to Africa.

On November 26, 1841, nearly three years after their abduction, the Africans departed New York City bound for home. Only 35 of them made it back. The others died at sea or while in custody.

The original 19th-century manuscripts from the Amistad case and our entire Black History collection are available to search for free this month on Fold3!

| Civil Rights Act of 1964 Facts

|

| Interesting Civil Rights Act of 1964 Facts: |

|---|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

Heart of Atlanta Hotel v. United States, Philips v. Martin Marietta Corp., and Pittsburgh Press Co. v. Pittsburgh Commission on Human Relations. |

|

|

| Although some aspects of voting problems were addressed in the Civil Rights Act of 1964, most of the barriers to black disenfranchisement in the southern states were dealt with in the Voting Rights Act of 1965.

softschools.com |

If you see any errors please feel free to comment… so many opinions on who actually came up with the idea of the Bill

You must be logged in to post a comment.