![]()

President Franklin D. Roosevelt signed the Social Security Bill into law on August 14, 1935, only 14 months after sending a special message to Congress on June 8, 1934, that promised a plan for social insurance as a safeguard “against the hazards and vicissitudes of life.” The 32-page Act was the culmination of work begun by the Committee on Economic Security (CES), created by the President on June 29, 1934, and became, as he said at the signing ceremony, “a cornerstone in a structure which is being built but is by no means complete. ” (For developments in the old-age benefits portion of the Act since 1935, see Martha A. McSteen, “Fifty Years of Social Security.”)

The President transmitted the Committee’s report to the 74th Congress on January 17, 1935, almost equally dividing the 14 months spanning the work of the Committee and the work of the Congress. Today, 50 years later, Wilbur J. Cohen, who was a 21-year-old research assistant to the Executive Director of the CES and later served as Secretary of Health, Education, and Welfare, writes: “If any piece of social legislation can be called historic or revolutionary, in breaking with the past and in terms of long run impact, it is the Social Security Act. ”

Although the Congress modified many details of the Economic Security Bill introduced on behalf of the CES, most of the programs recommended by the Committee were adopted. Earlier installments in this series have discussed the changes as they occurred during the legislative process.

The Social Security Act established two types of provisions for old-age security: (1) Federal aid to the States to enable them to provide cash pensions to their needy aged, and (2) a system of Federal old-age benefits for retired workers. The first measure was designed to provide immediate assistance to destitute aged individuals. The second was a preventive measure intended to reduce the extent of future dependency among the aged and to assure workers that their years of employment entitled them to a life income.

For needy persons already aged 65 or older, old-age assistance was provided, by title I, through Federal grants-in-aid to pay half the costs of the pensions, provided that the Federal share did not exceed $15 a month per person. In Mr. Cohen’s judgment, the most significant long-range congressional modification of the original proposal was the deletion of the condition that States should provide a “reasonable subsistence compatible with decency and health. ”

For the working population under age 65, the Social Security Act created, in title II, an “Old-Age Reserve Account” and authorized payments of old-age benefits from this account to eligible individuals upon attainment of age 65 or on January 1, 1942, whichever was later. The monthly benefit amount was determined by the total amount of wages earned in covered employment after 1936 and before age 65. The initial benefit formula was designed to give greater weight to the earnings of lower-paid workers and persons already middle-aged or older. The minimum monthly benefit was $10 and the maximum was $85.

Only the first $3,000 of annual salary from any one employer would be considered as counting toward the total of annual wages on which benefits would be computed. Less than 10 percent of the workers in commerce and industry earned more than this amount at that time. Large numbers of individuals were not covered, including the self-employed, agricultural and domestic service workers, casual laborers, employees of nonprofit organizations, and those subject to the Railroad Retirement Act of 1935.

There were no monthly survivors benefits. Rather, if a person had earned less than $2,000 in covered employment by age 65, he or she would receive a lump sum payment of 3.5 percent of total wages. Also, if an individual died after 1936 before reaching age 65, his or her estate would receive a lump sum amount equal to 3.5 percent of total covered wages.

Unemployment compensation, temporary cash payments to the involuntarily unemployed, was conceived by the CES as the “front line of defense” from dependency resulting from loss of earnings and as a means of maintaining purchasing power. The unemployment compensation provisions of the Social Security Act were quite similar to those recommended by the CES. The Act set up a Federal-State cooperative system, to be administered by the States, and provided financial assistance from the Federal Government to those States with laws approved by the Social Security Board. In 1935, only Wisconsin had enacted an unemployment program, but the Federal law provided an incentive for all States to establish such programs.

Other provisions of the Social Security Act included four programs recommended by the CES for promoting the health and welfare of children. These programs provided grants-in-aid to States for (1) financial aid to dependent children (ADC), (2) maternal and child health services (MCH), (3) services for crippled children (CCS), and (4) child welfare services (CWS). Further, the Congress strengthened vocational rehabilitation, amending a law enacted in 1920, by providing permanent rather than year-to-year authorizations. Congress also added a title providing grants to States for aid to needy blind individuals.

Finally, as recommended by the CES, the Act broadened public health services to all localities by authorizing $8 million in grants to States to assist in establishing and maintaining adequate public-health services including the training of personnel and provided an additional $2 million for the expansion of public health investigations by the Public Health Service. The Act thus tripled Federal public health expenditures and established a program for the extension of preventive public health services to the entire Nation.

The Act created a Social Security Board (SSB), not as a component of the Department of Labor, as the CES had proposed, but as an independent agency. This organization was to administer the old-age assistance and old-age benefits programs, unemployment compensation, aid to dependent children, and aid to the blind. The Children’s Bureau in the Department of Labor was to administer service programs for maternal and child health, crippled children, and child welfare. The Act did not change the administration of public health and vocational rehabilitation.

After signing the bill the President promptly sent the names of the three nominees for members of the SSB to the Senate: John G. Winant, former Republican Governor of New Hampshire, chairman; Vincent M. Miles, former Democratic National Committeeman from Arkansas; and Arthur J. Altmeyer, an Assistant Secretary of Labor who had served as Chairman of the Technical Advisory Board of the CES. They were all confirmed on August 23.

Congress adjourned, however, before approving a supplemental appropriations bill that included operating funds for the SSB. On the last day of the session, Senator Huey Long (D., La.) had filibustered a matter unrelated to social security until the session closed.

The next morning the President called a conference of key leaders, according to Mr. Altmeyer who was present, to see what could be done. John R. McCarl, the Comptroller General, proposed that, since the CES had been financed as a research project by the Federal Emergency Relief Administration (FERA), the SSB could be financed as a research project by the FERA to develop ways and means of putting the Social Security Act into operation.

Despite this inauspicious start, in 1969, J. Douglas Brown, who had been a consultant to the CES, could still write:

“To one who has participated in the planning of the social security system since its inception, the most remarkable outcome over the years is the degree to which fundamental concepts, hammered out in 1934, have guided the development of one of the largest ventures in social engineering in the world. The system remains, basically, national, compulsory, and contributory. Benefits are a matter of right…. Even if time were then available, I doubt that we could have anticipated what experience has shown to be feasible in building a more adequate social security system.”

References

Altmeyer, Arthur J., The Formative Years of Social Security. Madison: The University of Wisconsin Press, 1966.

Brown, J. Douglas, The Genesis of Social Security in America. Princeton, N.J.: Industrial Relations Section, Princeton University, 1969.

Cohen, Wilbur J., “The Development of the Social Security Act of 1935: Reflections Some Fifty Years Later,” Minnesota Law Review, December 1983.

Committee on Economic Security, The Factual Background of the Social Security Act as Summarized From Staff Reports to the Committee on Economic Security. Washington, D.C.: Social Security Board, 1937.

National Conference on Social Welfare, Fiftieth Anniversary Edition: The Report of the Committee on Economic Security of 1935 and Other Basic Documents Relating to the Development of the Social Security Act. Washington, D.C.: Project on the Federal Social Role, 1985.

This note is the eighth in a series tracing the development of the Security Act in Congress 50 years ago. It was prepared by Thomas E. Price, Office of Research, Statistics, and International Policy, Office of Policy, Social Security Administration.

ssa.gov

Story by Jesse Beckett

Today is Code Talker Day

To keep their plans a secret from the enemy during the fighting in WWII, the US famously employed Native American code talkers who communicated in their native languages. However, WWII was not the first time Native Americans were employed in this critical role. Their combat debut was actually WWI.

Keeping your communications a secret from the enemy is one of the most important tasks during a conflict. If an enemy can listen in to your communications, they can plan ahead and counter any moves you intend to make.

The development of modern computers received a huge boost during WWII when they were used to decrypt enemy-coded messages. In fact, the world’s first programmable, electronic, digital computer was created for this purpose.

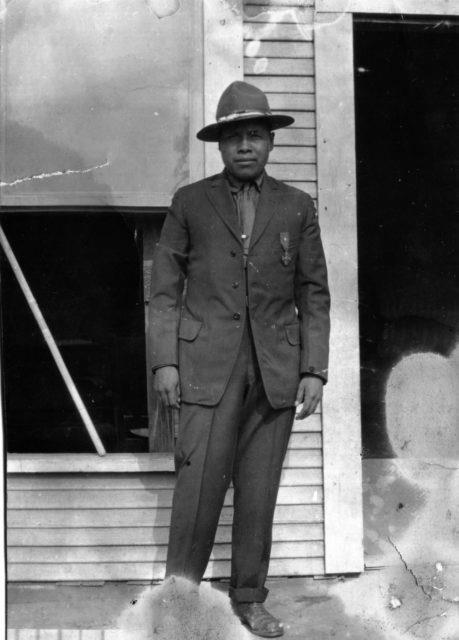

Photograph of Choctaw Joseph Oklahombi, a World War I Code Talker, early twentieth century. (Photo by Oklahoma Historical Society/Getty Images)© Provided by War History Online

The government of the Choctaw Nation asserts that the Choctaw were the first Native American code talkers to serve in the US military.

This took place in the 1918 Meuse-Argonne campaign in France. During this battle, the Germans had cracked Allied codes and tapped into their communication lines. Speaking great English, they continuously listened to radio messages. Even sending messages by hand was difficult, as the Germans were capturing on average one in every four runners.

One American officer, Colonel Alfred Wainwright Bloor, devised a clever way to overcome their communicational predicament after overhearing two Choctaw soldiers in his regiment having a conversation in their native language.

1521 – Present day Mexico City was captured by Spanish conqueror Hernando Cortez from the Aztec Indians.

1521 – Present day Mexico City was captured by Spanish conqueror Hernando Cortez from the Aztec Indians.

1704 – The Battle of Blenheim was fought during the War of the Spanish Succession, resulting in a victory for English and Austrian forces.

1792 – French revolutionaries took the entire French royal family and imprisoned them.

1784 – The United States Legislature met for the final time in Annapolis, MD.

1846 – The American Flag was raised for the first time in Los Angeles, CA.

1876 – The Reciprocity Treaty between the U.S. and Hawaii was ratified.

1889 – A patent for a coin-operated telephone was issued to William Gray.

1912 – The first experimental radio license was issued to St. Joseph’s College in Philadelphia, PA.

1931 – The first community hospital in the U.S. was dedicated in Elk City, OK.

1932 – Adolf Hitler refused to take the post of vice-chancellor of Germany. He said he was going to hold out “for all or nothing.”

1934 – Al Capp’s comic strip “L’il Abner” made its debut in newspapers.

1942 – Henry Ford unveiled his “Soybean Car.” It was a plastic-bodied car that weighed about 1000 lbs. less than a steel car.

1942 – Walt Disney’s “Bambi” opened at Radio City Music Hall in New York City, NY.

Disney movies, music and books

1959 – In New York, ground was broken on the $320 million Verrazano Narrows Bridge.

1960 – “Echo I,” a balloon satellite, allowed the first two-way telephone conversation by satellite to take place.

1961 – Berlin was divided by a barbed wire fence to halt the flight of refugees. Two days later work on the Berlin Wall began.

1979 – Lou Brock (St. Louis Cardinals) got his 3,000th career hit.

1986 – United States Football League standout Herschel Walker signed to play with the Dallas Cowboys of the National Football League.

1990 – Iraq transferred $3-4 billion in bullion, currency, and other goods seized from Kuwait to Baghdad.

On August 12, 1990, fossil hunter Susan Hendrickson discovers three huge bones jutting out of a cliff near Faith, South Dakota. They turn out to be part of the largest-ever Tyrannosaurus rex skeleton ever discovered, a 65 million-year-old specimen dubbed Sue, after its discoverer.

Amazingly, Sue’s skeleton was over 90 percent complete, and the bones were extremely well-preserved. Hendrickson’s employer, the Black Hills Institute of Geological Research, paid $5,000 to the land owner, Maurice Williams, for the right to excavate the dinosaur skeleton, which was cleaned and transported to the company headquarters in Hill City. The institute’s president, Peter Larson, announced plans to build a non-profit museum to display Sue along with other fossils of the Cretaceous period.

Source:

history.com

Skeleton of Tyrannosaurus rex discovered

HISTORY

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/skeleton-of-tyrannosaurus-rex-discovered

August 11, 2021

A&E Television Networks

August 10, 2021

November 24, 2009

You must be logged in to post a comment.