mr till was born on

(Photo: AP Photo/Chicago Tribune)

While visiting family in Money, Mississippi, 14-year-old Emmett Till, an African American from Chicago, is brutally murdered for flirting with a white woman four days earlier. His assailants–the white woman’s husband and her brother–made Emmett carry a 75-pound cotton-gin fan to the bank of the Tallahatchie River and ordered him to take off his clothes. The two men then beat him nearly to death, gouged out his eye, shot him in the head, and then threw his body, tied to the cotton-gin fan with barbed wire, into the river.

Till grew up in a working-class neighborhood on the south side of Chicago, and though he had attended a segregated elementary school, he was not prepared for the level of segregation he encountered in Mississippi. His mother warned him to take care because of his race, but Emmett enjoyed pulling pranks. On August 24, while standing with his cousins and some friends outside a country store in Money, Emmett bragged that his girlfriend back home was white. Emmett’s African American companions, disbelieving him, dared Emmett to ask the white woman sitting behind the store counter for a date. He went in, bought some candy, and on the way out was heard saying, “Bye, baby” to the woman. There were no witnesses in the store, but Carolyn Bryant–the woman behind the counter–claimed that he grabbed her, made lewd advances, and then wolf-whistled at her as he sauntered out.

Roy Bryant, the proprietor of the store and the woman’s husband, returned from a business trip a few days later and found out how Emmett had spoken to his wife. Enraged, he went to the home of Till’s great uncle, Mose Wright, with his brother-in-law J.W. Milam in the early morning hours of August 28. The pair demanded to see the boy. Despite pleas from Wright, they forced Emmett into their car. After driving around in the Memphis night, and perhaps beating Till in a toolhouse behind Milam’s residence, they drove him down to the Tallahatchie River.

Three days later, his corpse was recovered but was so disfigured that Mose Wright could only identify it by an initialed ring. Authorities wanted to bury the body quickly, but Till’s mother, Mamie Bradley, requested it be sent back to Chicago. After seeing the mutilated remains, she decided to have an open-casket funeral so that all the world could see what racist murderers had done to her only son. Jet, an African American weekly magazine, published a photo of Emmett’s corpse, and soon the mainstream media picked up on the story.

Less than two weeks after Emmett’s body was buried, Milam and Bryant went on trial in a segregated courthouse in Sumner, Mississippi. There were few witnesses besides Mose Wright, who positively identified the defendants as Emmett’s killers.

On September 23, the all-white jury deliberated for less than an hour before issuing a verdict of “not guilty,” explaining that they believed the state had failed to prove the identity of the body. Many people around the country were outraged by the decision and also by the state’s decision not to indict Milam and Bryant on the separate charge of kidnapping.

The Emmett Till murder trial brought to light the brutality of Jim Crow segregation in the South and was an early impetus of the African American civil rights movement.

history.com

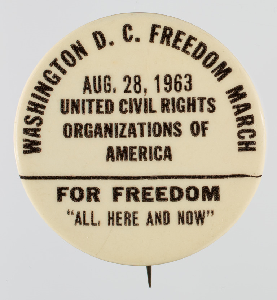

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr., delivered a speech to a massive group of civil rights marchers gathered around the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom brought together the nations most prominent civil rights leaders, along with tens of thousands of marchers, to press the United States government for equality. The culmination of this event was the influential and most memorable speech of Dr. King’s career. Popularly known as the “I have a Dream” speech, the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. influenced the Federal government to take more direct actions to more fully realize racial equality.

On August 28, 1963, Martin Luther King Jr., delivered a speech to a massive group of civil rights marchers gathered around the Lincoln Memorial in Washington DC. The March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom brought together the nations most prominent civil rights leaders, along with tens of thousands of marchers, to press the United States government for equality. The culmination of this event was the influential and most memorable speech of Dr. King’s career. Popularly known as the “I have a Dream” speech, the words of Martin Luther King, Jr. influenced the Federal government to take more direct actions to more fully realize racial equality.

You must be logged in to post a comment.