Category Archives: ~ Culture & History

Karen Davis… 20yr sentence for a nonviolent crime, serves 17yrs before clemency is implemented

Women’s History Month

Congratulations to Karen Davis who is NOW FREE thanks to the First Step Act.

DOB: 5/12/71

Age: 48

Race: Black

Marital Status: Married.

Children : Seven children, Timothy Benford, Nathan Benford, Willie Davis, Jr., Isadore Davis, Deonte Davis, Jazmine Davis, Brandon Davis.

Raised: Tennessee

Tried: Tennessee

I was exposed to the drug dealing business in my early teen years by my uncle, and then in my early twenties, drawn in further by my husband. I would sometimes transport drugs to complete their deals, but I was not an enthusiastic participant in this way of life. By the time I was 25 years old my husband was sent to prison for 3 years and left me at home with 5 boys to support. I started back dealing along with other family members, but I never acted as an introduction for anyone and I did not make the kind of sales or money that I was indicted for. My uncle was the first who eventually implicated me by calling at home multiple times telling me to take a plea and asking me to admit to things I knew were lies. I was not informed enough to know to take a plea and then it was withdrawn and I went to a speedy trial. I was portrayed as the leader, which is very far from being accurate. I received enhancements because of my priors and I was not granted a downward departure because I would not admit to lies that my uncle and cousin stated. Today, those who were the organizers and big dealers are out free while I am still incarcerated and paying my penalty.

Karen believes she deserves clemency because:

I acknowledge the mistakes I made, I have worked hard to change my way of thinking and acting and I need to return home for the sake of my 7 children. I have learned some valuable lessons while I have been in prison and I want to share my experiences and knowledge with others to help them avoid making the same mistakes I made. I have grown and evolved into a much more humble and diversified person with a passion to go out into society to make a difference in this world especially for those who may feel lost and wander this earth “not all who wander are always lost”. I have a fire that burns inside me to rebuild my life with the sincerest intentions to be the best I can be for my family, friends and those who may need someone who has a caring heart.

Future Plans: My future life plans are to obtain a job in a technology call center environment. I worked and learned quite a bit while working in the UNICOR call center for 8 years. I was an operator for several years and then worked my way up to a clerk position. I would also like to continue with my education using government grants that may be available. I would like to be located in the Atlanta area and I want to be part of the EPIC family and assist with the work of CAN-DO to help others who are still incarcerated. I trust that God will reveal to me His Will for my life and use me in ways that He sees fit.

Charge(s): Conspiracy to Distribute and Possess with Intent to Distribute 50 grams or more of cocaine. 21 USC 843: Use of a Telephone to Facilitate Commission of a Conspiracy to distribute Cocaine and Marijuana.

Health Status: High blood pressure

Sentence: 20 years

Date Sentence Started: 7/22/2003

Years served: 17 years

Release Date: 10/22/2020. (NOW FREE)

Will Live: Atlanta, GA

Charge(s): Conspiracy to Distribute and Possess with Intent to Distribute 50 grams or more of cocaine. 21 USC 843: Use of a Telephone to Facilitate Commission of a Conspiracy to distribute Cocaine and Marijuana.

Priors: Possession of marijuana, simple assault, selling or delivering cocaine.

Prison Conduct: Clear record.

Supporters: CAN-DO Foundation, The LOHM, FEDFAM4LIFE, my family, my church community, many friends.

Address:

FCI PEKIN, SATELLITE CAMP

P.O. BOX 5000

PEKIN, IL 61555

Prison Accomplishments: Karen mentors new women who enter the prison, participated in the Cancer Walk, and organizes sports events. She consistently receives “outstanding work evaluation” at UNICOR.

Courses Completed: Completed the 40 hour drug program, Reach 1-Teach 1, AIDS awareness, Wellness, psychology, business education, budgeting and money management courses.

Source: candoclemency.com

Ida B. Wells-Barnett Marched over 100yrs ago for – Women’s voting rights- Black History is American history

b. 7/16/1862

b. 7/16/1862

1913

100 years ago

Social activist Ida B. Wells-Barnett marches in Washington, D.C., with 5,000 suffragettes in a protest supporting women’s voting rights.

African American journalist and anti-lynching crusader Ida B. Wells (1862-1931) was born to slaves at Holly Springs, Missouri. Following the Civil War, as lynchings became prevalent, Wells traveled extensively, founding anti-lynching societies and black women’s clubs.

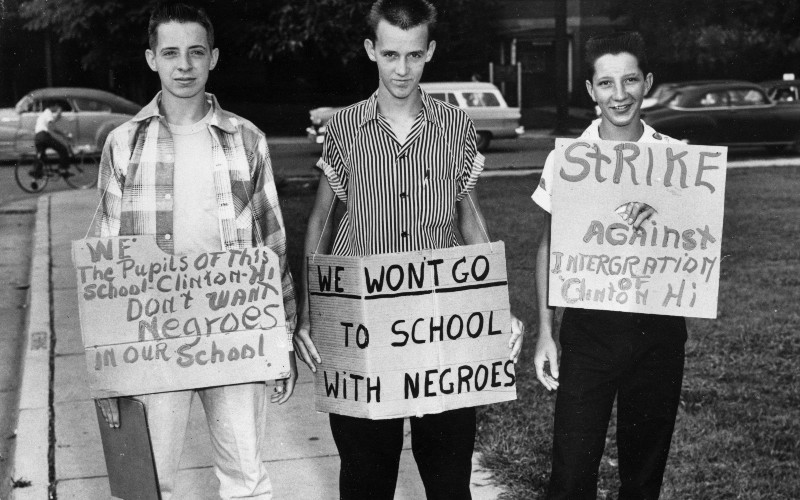

Brown V Board of Education ~~ Equality & Opportunity – Women’s History Month

Brown v. Board of Education (1954)

PBS.org

![]()

Brown v. Board of Education (1954), now acknowledged as one of the greatest Supreme Court decisions of the 20th century, unanimously held that the racial segregation of children in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment. Although the decision did not succeed in fully desegregating public education in the United States, it put the Constitution on the side of racial equality and galvanized the nascent civil rights movement into a full revolution.

In 1954, large portions of the United States had racially segregated schools, made legal by Plessy v. Ferguson (1896), which held that segregated public facilities were constitutional so long as the black and white facilities were equal to each other. However, by the mid-twentieth century, civil rights groups set up legal and political, challenges to racial segregation. In the early 1950s, NAACP lawyers brought class action lawsuits on behalf of black schoolchildren and their families in Kansas, South Carolina, Virginia, and Delaware, seeking court orders to compel school districts to let black students attend white public schools.

One of these class actions, Brown v. Board of Education was filed against the Topeka, Kansas school board by representative-plaintiff Oliver Brown, parent of one of the children denied access to Topeka’s white schools. Brown claimed that Topeka’s racial segregation violated the Constitution’s Equal Protection Clause because the city’s black and white schools were not equal to each other and never could be. The federal district court dismissed his claim, ruling that the segregated public schools were “substantially” equal enough to be constitutional under the Plessy doctrine. Brown appealed to the Supreme Court, which consolidated and then reviewed all the school segregation actions together. Thurgood Marshall, who would in 1967 be appointed the first black justice of the Court, was chief counsel for the plaintiffs.

Thanks to the astute leadership of Chief Justice Earl Warren, the Court spoke in a unanimous decision written by Warren himself. The decision held that racial segregation of children in public schools violated the Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment, which states that “no state shall make or enforce any law which shall … deny to any person within its jurisdiction the equal protection of the laws.” The Court noted that Congress, when drafting the Fourteenth Amendment in the 1860s, did not expressly intend to require integration of public schools. On the other hand, that Amendment did not prohibit integration. In any case, the Court asserted that the Fourteenth Amendment guarantees equal education today. Public education in the 20th century, said the Court, had become an essential component of a citizen’s public life, forming the basis of democratic citizenship, normal socialization, and professional training. In this context, any child denied a good education would be unlikely to succeed in life. Where a state, therefore, has undertaken to provide universal education, such education becomes a right that must be afforded equally to both blacks and whites.

Were the black and white schools “substantially” equal to each other, as the lower courts had found? After reviewing psychological studies showing black girls in segregated schools had low racial self-esteem, the Court concluded that separating children on the basis of race creates dangerous inferiority complexes that may adversely affect black children’s ability to learn. The Court concluded that, even if the tangible facilities were equal between the black and white schools, racial segregation in schools is “inherently unequal” and is thus always unconstitutional. At least in the context of public schools, Plessy v. Ferguson was overruled. In the Brown II case a decided year later, the Court ordered the states to integrate their schools “with all deliberate speed.”

Opposition to Brown I and II reached an apex in Cooper v. Aaron (1958), when the Court ruled that states were constitutionally required to implement the Supreme Court’s integration orders. Widespread racial integration of the South was achieved by the late 1960s and 1970s. In the meantime, the equal protection ruling in Brown spilled over into other areas of the law and into the political arena as well. Scholars now point out that Brown v. Board was not the beginning of the modern civil rights movement, but there is no doubt that it constituted a watershed moment in the struggle for racial equality in America.

History of Brown v. Board of Education

UScourts.gov

- Re-enactment – Use a readers theater format to re-enact the case.

- History of Brown v. Board of Education – Learn about the background and similar cases.

- Justice Thurgood Marshall Profile – Read about Justice Thurgood Marshall’s early life, education, and legal career.

The Plessy Decision ~~ Separate but Equal?

Although the Declaration of Independence stated that “All men are created equal,” due to the institution of slavery, this statement was not to be grounded in law in the United States until after the Civil War (and, arguably, not completely fulfilled for many years thereafter). In 1865, the Thirteenth Amendment was ratified and finally put an end to slavery. Moreover, the Fourteenth Amendment (1868) strengthened the legal rights of newly freed slaves by stating, among other things, that no state shall deprive anyone of either “due process of law” or of the “equal protection of the law.” Finally, the Fifteenth Amendment (1870) further strengthened the legal rights of newly freed slaves by prohibiting states from denying anyone the right to vote due to race.

Despite these Amendments, African Americans were often treated differently than whites in many parts of the country, especially in the South. In fact, many state legislatures enacted laws that led to the legally mandated segregation of the races. In other words, the laws of many states decreed that blacks and whites could not use the same public facilities, ride the same buses, attend the same schools, etc. These laws came to be known as Jim Crow laws. Although many people felt that these laws were unjust, it was not until the 1890s that they were directly challenged in court. In 1892, an African-American man named Homer Plessy refused to give up his seat to a white man on a train in New Orleans, as he was required to do by Louisiana state law. For this action he was arrested. Plessy, contending that the Louisiana law separating blacks from whites on trains violated the “equal protection clause” of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution, decided to fight his arrest in court. By 1896, his case had made it all the way to the United States Supreme Court. By a vote of 8-1, the Supreme Court ruled against Plessy. In the case of Plessy v. Ferguson, Justice Henry Billings Brown, writing the majority opinion, stated that:

“The object of the [Fourteenth] amendment was undoubtedly to enforce the equality of the two races before the law, but in the nature of things it could not have been intended to abolish distinctions based upon color, or to endorse social, as distinguished from political, equality. . . If one race be inferior to the other socially, the Constitution of the United States cannot put them upon the same plane.”

The lone dissenter, Justice John Marshal Harlan, interpreting the Fourteenth Amendment another way, stated, “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among citizens.” Justice Harlan’s dissent would become a rallying cry for those in later generations that wished to declare segregation unconstitutional.

Sadly, as a result of the Plessy decision, in the early twentieth century the Supreme Court continued to uphold the legality of Jim Crow laws and other forms of racial discrimination. In the case of Cumming v. Richmond (Ga.) County Board of Education (1899), for instance, the Court refused to issue an injunction preventing a school board from spending tax money on a white high school when the same school board voted to close down a black high school for financial reasons. Moreover, in Gong Lum v. Rice (1927), the Court upheld a school’s decision to bar a person of Chinese descent from a “white” school.

The Road to Brown

(Note: Some of the case information is from Patterson, James T. Brown v. Board of Education: A Civil Rights Milestone and Its Troubled Legacy. Oxford University Press; New York, 2001.)

Early Cases

Despite the Supreme Court’s ruling in Plessy and similar cases, many people continued to press for the abolition of Jim Crow and other racially discriminatory laws. One particular organization that fought for racial equality was the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) founded in 1909. For about the first 20 years of its existence, it tried to persuade Congress and other legislative bodies to enact laws that would protect African Americans from lynchings and other racist actions. Beginning in the 1930s, though, the NAACP’s Legal Defense and Education Fund began to turn to the courts to try to make progress in overcoming legally sanctioned discrimination. From 1935 to 1938, the legal arm of the NAACP was headed by Charles Hamilton Houston. Houston, together with Thurgood Marshall, devised a strategy to attack Jim Crow laws by striking at them where they were perhaps weakest—in the field of education. Although Marshall played a crucial role in all of the cases listed below, Houston was the head of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund while Murray v. Maryland and Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada were decided. After Houston returned to private practice in 1938, Marshall became head of the Fund and used it to argue the cases of Sweat v. Painter and McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education.

Murray v. Maryland (1936)

Disappointed that the University of Maryland School of Law was rejecting black applicants solely because of their race, beginning in 1933 Thurgood Marshall (who was himself rejected from this law school because of its racial acceptance policies) decided to challenge this practice in the Maryland court system. Before a Baltimore City Court in 1935, Marshall argued that Donald Gaines Murray was just as qualified as white applicants to attend the University of Maryland’s School of Law and that it was solely due to his race that he was rejected. Furthermore, he argued that since the “black” law schools which Murray would otherwise have to attend were nowhere near the same academic caliber as the University’s law school, the University was violating the principle of “separate but equal.” Moreover, Marshall argued that the disparities between the “white” and “black” law schools were so great that the only remedy would be to allow students like Murray to attend the University’s law school. The Baltimore City Court agreed and the University then appealed to the Maryland Court of Appeals. In 1936, the Court of Appeals also ruled in favor of Murray and ordered the law school to admit him. Two years later, Murray graduated.

Missouri ex rel Gaines v. Canada (1938)

Beginning in 1936, the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund decided to take on the case of Lloyd Gaines, a graduate student of Lincoln University (an all-black college) who applied to the University of Missouri Law School but was denied because of his race. The State of Missouri gave Gaines the option of either attending an all-black law school that it would build (Missouri did not have any all-black law schools at this time) or having Missouri help to pay for him to attend a law school in a neighboring state. Gaines rejected both of these options, and, employing the services of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, he decided to sue the state in order to attend the University of Missouri’s law school. By 1938, his case reached the U.S. Supreme Court, and, in December of that year, the Court sided with him. The six-member majority stated that since a “black” law school did not currently exist in the State of Missouri, the “equal protection clause” required the state to provide, within its boundaries, a legal education for Gaines. In other words, since the state provided legal education for white students, it could not send black students, like Gaines, to school in another state.

Sweat v. Painter (1950)

Encouraged by their victory in Gaines’ case, the NAACP continued to attack legally sanctioned racial discrimination in higher education. In 1946, an African American man named Heman Sweat applied to the University of Texas’ “white” law school. Hoping that it would not have to admit Sweat to the “white” law school if a “black” school already existed, elsewhere on the University’s campus, the state hastily set up an underfunded “black” law school. At this point, Sweat employed the services of Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund and sued to be admitted to the University’s “white” law school. He argued that the education that he was receiving in the “black” law school was not of the same academic caliber as the education that he would be receiving if he attended the “white” law school. When the case reached the U.S. Supreme Court in 1950, the Court unanimously agreed with him, citing as its reason the blatant inequalities between the University’s law school (the school for whites) and the hastily erected school for blacks. In other words, the “black” law school was “separate,” but not “equal.” Like the Murray case, the Court found the only appropriate remedy for this situation was to admit Sweat to the University’s law school.

McLaurin v. Oklahoma Board of Regents of Higher Education (1950)

In 1949, the University of Oklahoma admitted George McLaurin, an African American, to its doctoral program. However, it required him to sit apart from the rest of his class, eat at a separate time and table from white students, etc. McLaurin, stating that these actions were both unusual and resulting in adverse effects on his academic pursuits, sued to put an end to these practices. McLaurin employed Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund to argue his case, a case which eventually went to the U.S. Supreme Court. In an opinion delivered on the same day as the decision in Sweat, the Court stated that the University’s actions concerning McLaurin were adversely affecting his ability to learn and ordered that they cease immediately.

Brown v. Board of Education (1954, 1955)

The case that came to be known as Brown v. Board of Education was actually the name given to five separate cases that were heard by the U.S. Supreme Court concerning the issue of segregation in public schools. These cases were Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka, Briggs v. Elliot, Davis v. Board of Education of Prince Edward County (VA.), Boiling v. Sharpe, and Gebhart v. Ethel. While the facts of each case are different, the main issue in each was the constitutionality of state-sponsored segregation in public schools. Once again, Thurgood Marshall and the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund handled these cases.

Although it acknowledged some of the plaintiffs’/plaintiffs claims, a three-judge panel at the U.S. District Court that heard the cases ruled in favor of the school boards. The plaintiffs then appealed to the U.S. Supreme Court.

When the cases came before the Supreme Court in 1952, the Court consolidated all five cases under the name of Brown v. Board of Education. Marshall personally argued the case before the Court. Although he raised a variety of legal issues on appeal, the most common one was that separate school systems for blacks and whites were inherently unequal, and thus violate the “equal protection clause” of the Fourteenth Amendment to the U.S. Constitution. Furthermore, relying on sociological tests, such as the one performed by social scientist Kenneth Clark, and other data, he also argued that segregated school systems had a tendency to make black children feel inferior to white children, and thus such a system should not be legally permissible.

Meeting to decide the case, the Justices of the Supreme Court realized that they were deeply divided over the issues raised. While most wanted to reverse Plessy and declare segregation in public schools to be unconstitutional, they had various reasons for doing so. Unable to come to a solution by June 1953 (the end of the Court’s 1952-1953 term), the Court decided to rehear the case in December 1953. During the intervening months, however, Chief Justice Fred Vinson died and was replaced by Gov. Earl Warren of California. After the case was reheard in 1953, Chief Justice Warren was able to do something that his predecessor had not—i.e. bring all of the Justices to agree to support a unanimous decision declaring segregation in public schools unconstitutional. On May 14, 1954, he delivered the opinion of the Court, stating that “We conclude that in the field of public education the doctrine of ‘separate but equal’ has no place. Separate educational facilities are inherently unequal. . .”

Expecting opposition to its ruling, especially in the southern states, the Supreme Court did not immediately try to give direction for the implementation of its ruling. Rather, it asked the attorney generals of all states with laws permitting segregation in their public schools to submit plans for how to proceed with desegregation. After still more hearings before the Court concerning the matter of desegregation, on May 31, 1955, the Justices handed down a plan for how it was to proceed; desegregation was to proceed with “all deliberate speed.” Although it would be many years before all segregated school systems were to be desegregated, Brown and Brown II (as the Courts plan for how to desegregate schools came to be called) were responsible for getting the process underway.

resource: PBS.org UScourts.gov Dec 9, 1952 – May 17, 1954

60 plus years and the struggle for Equity and Opportunity continues! In this 21st Century we still have folks pushing separate – Nativegrl77

1779 – Congress creates U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

On March 11, 1779, Congress establishes the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers to help plan, design and prepare environmental and structural facilities for the U.S. Army. Made up of civilian workers, members of the Continental Army and French officers, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers …read more

Today, the U. S. Army Corps of Engineers is made up of more than 35,000 civilian and enlisted men and women. In recent years, the Corps has worked on rebuilding projects in Afghanistan and Iraq, as well as the reconstruction of the city of New Orleans in the wake of Hurricane Katrina

1779March 11

Citation Information

Article Title

Congress establishes the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

AuthorHistory.com Editors

Website Name

HISTORY

URL

https://www.history.com/this-day-in-history/congress-establishes-the-u-s-army-corps-of-engineers

Access Date

March 11, 2022

Publisher

A&E Television Networks

Last Updated

March 9, 2021

Original Published Date

November 13, 2009

BY

You must be logged in to post a comment.