White House, drawing by James Hoban

Drawing of the elevation of the White House by James Hoban, 1792; in the Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore.Courtesy of the Maryland Historical Society, Baltimore

For an African American, it was a challenge to patent an invention, especially in the late 1800s. However, Isaac R. Johnson succeeded in this challenge when he patent the bicycle frame on October 10, 1899.[1]

Isaac R. Johnson was born in New York sometime during 1812. While he was not the first person to invent the bicycle frame, he was the first African American to invent and patent the bicycle frame, especially a frame which could be folded or taken apart for easy storage.

In fact, Isaac Johnson’s version of the bicycle frame is similar to the version we ride today as the bicycles we use today have the same pattern, they just do not fold up. Johnson’s version was a frame which could be folded and stored in small places, it was often used while traveling and on vacation.[2]

Isaac R. Johnson originally filed for the patent in April of 1899 and it was given the publication number: US634823 A. The only information we really have about Isaac R. Johnson is from the information he filled out when he filed his patent.

Through this paperwork, we know that he lived in Manhattan, New York. The paperwork also states that this bicycle frame is an improved version from any previous bicycle frames due to its ability to be taken apart and placed in a truck or other small storage area.

The bicycle also came with instructions, which would describe each piece of the bicycle frame, such as figure 1 was a side elevation of a bicycle of vehicle and figure 2 was the sectional side elevation of figure 1.[3]

urbanintellectuals.com

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

John A. Corry. The First Lincoln-Douglas Debates, October 1854. Philadelphia.: Xlibris, 2008. Pp. 219.

Roy Morris Jr. The Long Pursuit: Abraham Lincoln’s Thirty-Year Struggle with Stephen Douglas for the Heart and Soul of America. Washington, D.C.: Smithsonian Books, 2008. Pp. xiv, 220.

1858 Oct 7, Lincoln and Douglas held their 5th debate in Galesburg, Ill., on the Knox College campus.

(SFEM, 10/29/00, p.8)(ON, 4/08, p.2)

Although interest in the topic has never waned, the sesquicentennial of the 1858 debates between Stephen A. Douglas and Abraham Lincoln will certainly increase attention to the best-known formal exchange in American political history. Already plans have been announced to commemorate the debates at the original locations fourteen years after C-SPAN offered national coverage for its reenactments. Allen C. Guezlo’s Lincoln and Douglas: The Debates That Defined America, published this year, is seen by some as the topic’s definitive treatment.

The historical context for the debates is further aided by the publication of two other books. Roy Morris Jr.’s The Long Pursuit, by focusing on the three-decade competition between the debaters, includes a serious examination of the 1858 meetings. John A. Corry’s The First Lincoln-Douglas Debates does not, instead highlighting what he argues is the prequel, a series of speeches both gave in the fall of 1854. In that campaign, Lincoln worked to succeed James Shields, the incumbent U.S. senator. Douglas fought to rally voters behind his Kansas-Nebraska Act and save Shields’s seat.

Corry’s book largely focuses on recounting and analyzing Lincoln’s remarks in the abbreviated debate series of 1854, though he credits location of a Douglas campaign speech as completing the sources he needed for the book. He is not above arguing with Douglas in his footnotes, as he does on page 80 when discussing Douglas’s October 3, 1854, speech in the Illinois state capitol.

Some counterfactual history comes into play during the last pages as Corry poses a scenario in which Lincoln—rather than Lyman Trumbull—succeeds Shields and joins Douglas in the Senate. Without the 1858 debates, would Lincoln still have emerged as a national figure? Corry answers yes, citing Lincoln’s debating skills and ability to hold his own against stiff competition.

The Long Pursuit, however, does a much better job of demonstrating the competition that produced a man able to best the national political figures he brought into his administration. Morris does so by treating Douglas seriously and demonstrating instances where Lincoln was, perhaps, not quite the pedestal-perching figure some assume him to be. Morris wastes no time in outlining his thesis—”Had it not been for Douglas, Lincoln would have remained merely a good trial lawyer in Springfield, Illinois, known locally for his droll sense of humor, bad jokes, and slightly nutty wife” (xi–xii).

The thirty-year struggle between the two men was largely one-sided until the last six, as Douglas achieved national prominence and Lincoln’s ambition, the “little engine that knew no rest,” in William Herndon’s words, sputtered in frustration and disappointment. Not surprisingly, at times such feelings may have led Lincoln to say things he knew not to be true. Morris provides an example from Lincoln’s famed “Lost Speech” in Bloomington on May 29, 1856. Lincoln erroneously alleged that Douglas supported Southern fireater George Fitzhugh’s assertion that slavery was such a good idea it ought to be extended to white laborers. “Old habits die hard and Lincoln could not resist whacking ‘Judge Douglas’ whenever he got the chance” (87).

And what of old John Brown, who Lincoln described as a man of “great courage and rare unselfishness” after his ill-fated raid on Harper’s Ferry while at the same time trying to absolve himself and the Republican Party of any responsibility for the fiasco. Yet, Morris notes, Lincoln’s rhetoric decried a “house divided” and the evil of slavery. “When an extremist such as Brown took such warnings seriously and set out to redress the evil in the best way he knew how … neither Lincoln nor any other northern leader could convincingly plead complete innocence” (128).

It would be a serious mistake to view Morris’s volume as an “anti-Lincoln” work. He clearly demonstrates Lincoln’s better understanding of the fundamental changes sweeping American politics in the wake of the Kansas-Nebraska Act. And while Douglas and Lincoln were clearly rivals—and intense ones—Morris also provides examples of mutual respect and friendship, such as when, at Lincoln’s request, Douglas wrote a personal letter to the president of Harvard, “immeasurably” aiding Robert Lincoln’s admission (135).

Morris grasps a basic fact. To really understand Lincoln and his greatness, one must deal with Douglas. The melodramatic role as “villain” in the Lincoln story sometimes assigned Douglas undermines rather than enhances the sixteenth president’s remarkable story. Building upon earlier scholars such as Robert W. Johannsen (whom he acknowledges), Morris gives us a more realistic—and therefore more useful—picture of the politics that produced two remarkable men.

Morris provides not only a readable book but a valuable one to historians. He provides a clear explanation of why the famed 1858 debates still capture our imaginations and why, amid all the obscure squabbling about who said what and where contained in the exchanges, they still speak to us. And how, in their own time, the competition between two migrants to the Prairie State, “helped define and determine the course of American politics during its most convulsive era” (xiv).

Why do historians as well as readers in general continue to revisit the well-trod ground of those 1858 debates? Anyone who has read the debates soon realizes that the classic image of the confrontations is leavened by petty disputations, things all-too-familiar to our own politics. Amid all the obscure accusations and counter-charges, however, are some timeless exchanges. It is those that draw us back.

The Douglas-Lincoln disagreement, most markedly illustrated in 1858 but spilling beyond that year in both directions, was fundamentally about the nature of democracy.

Douglas, Morris argues, believed in the supremacy of majority rule, Lincoln in the right of the individual. “One way or another, it is a debate that still reverberates in American society” (xiii).

POSTED BY M. SWIFT – OCTOBER 5, 2021 – BLACK POLITICS, RACISM, RECONSTRUCTION

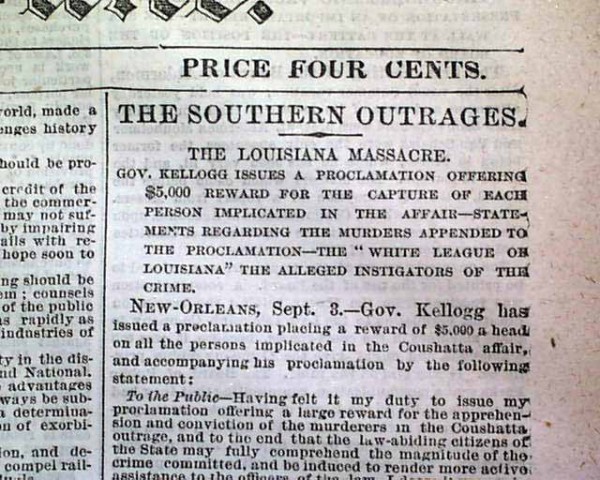

The Coushatta Massacre took place in August 1874 where the White League targeted Republican politicians presiding over Red River Parish and freedmen in the area. It would be the arrival of carpetbagger and Union vet Marshall H. Twitchell, his relationship with the freed Black community, and his position of power that ignited the league’s terror campaign in the parish.

At this time, Black people of note and carpetbaggers are now in state legislature. They also hold office in a number of town offices throughout the south. One of them was Marshall H. Twitchell, a white captain for the U.S. Army’s Company H, the 109th Colored Infantry. He was originally a provost marshal of the Red River branch of the Freedman Bureau.

While in Red River, he married a local Black woman named Adele Coleman. To provide for his family, the Vermont-born Twitchell learns to farm cotton after being taught by the Coleman family. The tensions began as this northern-born Union veteran began to accumulate land and influence in political power. He is elected to the Louisiana Senate as a Republican and put his brothers and brothers-in-law in positions of power.

For the complete article

blackthen.com

Reference

–http://www.knowlouisiana.org/entry/coushatta-massacre

1813 – Shawnee Indian Chief Tecumseh was defeated and killed during the War of 1812. Regarded as one of the greatest American Indians, he was a powerful orator who defended his people against white settlement. When the War of 1812 broke out, he joined the British as a brigadier general and was killed at the Battle of the Thames in Ontario.

1877 – Following a 1,700-mile retreat, Chief Joseph of the Nez Perce Indians surrendered to U.S. Cavalry troops at Bear’s Paw near Chinook, Montana. “From where the sun now stands, I will fight no more forever,” he declared.

1908 – Bulgaria proclaimed its independence from the Ottoman Empire.

1910 – Portugal became a republic following a successful revolt against King Manuel II.

, 1938 – Czech President Dr. Eduard Benes resigned and fled abroad amid threats from Adolf Hitler.

1964 – The largest mass escape since the construction of the Berlin Wall occurred as 57 East German refugees escaped to West Berlin after tunneling beneath the wall.

1986 – Former U.S. Marine Eugene Hasenfus was captured by Nicaraguan Sandinistas after a plane carrying arms for the Nicaraguan rebels (Contras) was shot down over Nicaragua. This marked the beginning of the “Iran-Contra” controversy resulting in Congressional hearings and a major scandal for the Reagan White House after it was revealed that money from the sale of arms to Iran was used to fund covert operations in Nicaragua.

You must be logged in to post a comment.