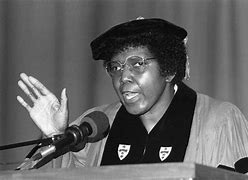

Barbara C. Jordan

1936–1996

Barbara Jordan emerged as an eloquent and powerful interpreter of the Watergate impeachment investigation at a time when many Americans despaired about the Constitution and the country. As one of the first African Americans elected from the Deep South since 1898 and the first black Congresswoman ever from that region, Jordan lent added weight to her message by her very presence on the House Judiciary Committee.

Barbara Charline Jordan was born in Houston, Texas, on February 21, 1936, one of three daughters of Benjamin M. Jordan and Arlyne Patten Jordan. Benjamin Jordan, a graduate of Tuskegee Institute, worked in a local warehouse before becoming pastor of Good Hope Missionary Baptist Church, which his family had long attended. Arlyne Jordan was an accomplished public speaker. Barbara Jordan was educated in the Houston public schools and graduated from Phyllis Wheatley High School in 1952. She earned a B.A. from Texas Southern University in 1956 and a law degree from Boston University in 1959. That same year she was admitted to the Massachusetts and Texas bars, and she began to practice law in Houston in 1960. To supplement her income (she worked temporarily out of her parents’ home), Jordan was employed as an administrative assistant to a county judge.1

Barbara Jordan’s political turning point occurred when she worked on the John F. Kennedy presidential campaign in 1960. She eventually helped manage a highly organized get–out–the–vote program that served Houston’s 40 African–American precincts. In 1962 and 1964, Jordan ran for the Texas house of representatives but lost both times, so in 1966 she ran for the Texas senate when court–enforced redistricting created a constituency that consisted largely of minority voters. Jordan won, defeating a white liberal and becoming the first African–American state senator in the U.S. since 1883 as well as the first black woman ever elected to that body.2 The other 30 (male, white) senators received her coolly, but Jordan won them over as an effective legislator who pushed through bills establishing the state’s first minimum wage law, antidiscrimination clauses in business contracts, and the Texas Fair Employment Practices Commission. On March 28, 1972, Jordan’s peers elected her president pro tempore of the Texas senate, making her the first black woman in America to preside over a legislative body. In seconding the nomination, one of Jordan’s male colleagues on the other side of the chamber stood, spread his arms open, and said, “What can I say? Black is beautiful.”3 One of Jordan’s responsibilities as president pro tempore was to serve as acting governor when the governor and lieutenant governor were out of the state. When Jordan filled that largely ceremonial role on June 10, 1972, she became the first black chief executive in the nation.

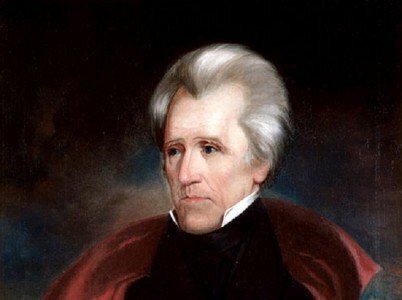

In 1971, Jordan entered the race for the Texas congressional seat encompassing downtown Houston. The district had been redrawn after the 1970 Census and was composed of a predominantly African–American and Hispanic–American population. In the 1972 Democratic primary, Jordan faced Curtis Graves, another black state legislator, who attacked her for being too close to the white establishment. Jordan blunted Graves’s charges with her legislative credentials. “I’m not going to Washington and turn things upside down in a day,” she told supporters at a rally. “I’ll only be one of 435. But the 434 will know I am there.”4 Jordan took the primary with 80 percent of the vote. In the general election, against Republican Paul Merritt, she won 81 percent of the vote. Along with Andrew Young of Georgia, Jordan became the first African American in the 20th century elected to Congress from the Deep South. In the next two campaign cycles, Jordan overwhelmed her opposition, capturing 85 percent of the total vote in both general elections.5

Representative Jordan’s political philosophy from her days in the state legislature led her to focus on local issues. Civil rights and women’s rights activists sometimes criticized her when she chose to favor her community interests rather than theirs. She followed this pattern in the House. “I sought the power points,” she once said. “I knew if I were going to get anything done, [the congressional and party leaders] would be the ones to help me get it done.”6 Jordan was reluctant to commit herself fully to any one interest group or caucus, such as the Congressional Black Caucus (CBC), of which she was a member. House women met informally too, but Jordan’s attendance at those meetings was irregular, and she was noncommittal on most issues that were brought before the group. She was especially careful not to attach herself too closely to an agenda she had little control over that might impinge on her ability to navigate and compromise within the institutional power structure. “I am neither a black politician nor a woman politician,” Jordan said in 1975. “Just a politician, a professional politician.”7

In both her Texas legislative career and in the U.S. House, Jordan made the conscious decision to pursue power within the established system. One of her first moves in Congress was to establish relations with Members of the Texas delegation, which had strong institutional connections. Her attention to influence inside the House was demonstrated by where she sat in the House Chamber’s large, theater–style seating arrangement. CBC members traditionally sat to the far left of the chamber, but Jordan chose to sit near the center aisle because she could hear better, be seen by the presiding officer, and save an open seat for colleagues who wanted to stop and chat. Her seating preference as well as her loyalty to the Texas delegation agitated fellow CBC members, but both were consistent with Jordan’s model of seeking congressional influence.8

Jordan also believed that an important committee assignment, one where she would be unique because of her gender and race, would magnify her influence. Thus, she disregarded suggestions that she accept a seat on the Education and Labor Committee, and used her connection with Texan Lyndon Johnson—she had been his guest at the White House during her time as a state legislator—to secure a plum committee assignment on the Judiciary Committee. Securing former President Johnson’s intercession with Wilbur Mills of Arkansas, the chairman of the Committee on Committees, she landed a seat on the Judiciary Committee, where she served for her three terms in the House. In the 94th and 95th Congresses (1975–1979), she was also assigned to the Committee on Government Operations.

It was as a freshman Member of the Judiciary Committee, however, that Jordan earned national recognition. In the summer of 1974, as the committee considered articles of impeachment against President Richard M. Nixon for crimes associated with the Watergate scandal, Jordan delivered opening remarks that shook the committee room and the large television audience tuned in to the proceedings. “My faith in the Constitution is whole, it is complete, it is total,” Jordan said. “I am not going to sit here and be an idle spectator to the diminution, the subversion, the destruction of the Constitution.” She then explained the reasoning behind her support of each of the five articles of impeachment against President Nixon. In conclusion, Jordan said that if her fellow committee members did not find the evidence compelling enough, “then perhaps the eighteenth–century Constitution should be abandoned to a twentieth–century paper shredder.”9 Reaction to Jordan’s statement was overwhelming. Jordan recalled that people swarmed around her car after the hearings to congratulate her. Impressed by her articulate reasoning and her knowledge of the law, many people sent the Texas Representative letters of praise. One person even posted a message on a series of billboards in Houston: “Thank you, Barbara Jordan, for explaining the Constitution to us.”10 The Watergate impeachment hearings helped create Jordan’s reputation as a respected national politician.

From her first days in Congress, Jordan encouraged colleagues to extend the federal protection of civil rights to more Americans. She introduced civil rights amendments to legislation authorizing law enforcement assistance grants and joined seven other members on the Judiciary Committee in opposing Gerald R. Ford’s nomination as Vice President, citing a mediocre civil rights record. In 1975, when Congress voted to extend the Voting Rights Act of 1965, Jordan sponsored legislation that broadened the provisions of the act to include Hispanic Americans, Native Americans, and Asian Americans. Although she voted for busing to enforce racial desegregation in public schools, she was one of the few African–American Members of Congress to question the utility of the policy.11

Jordan’s talent as a speaker continued to contribute to her national profile. In 1976, she became the first woman and the first African–American keynote speaker at a Democratic National Convention. Appearing after a subdued speech by Ohio Senator John Glenn, Jordan energized the convention with her oratory. “We are a people in search of a national community,” she told the delegates, “attempting to fulfill our national purpose, to create and sustain a society in which all of us are equal…. We cannot improve on the system of government, handed down to us by the founders of the Republic, but we can find new ways to implement that system and to realize our destiny.”12 Amid the historical perspective of the national bicentennial, and in the aftermath of the Vietnam War and Watergate, Jordan’s message, like her commanding voice, resonated with Americans. She campaigned widely for Democratic presidential candidate James Earl (Jimmy) Carter, who defeated President Ford in the general election. Though Carter later interviewed Jordan for a Cabinet position, he did not offer her the position of U.S. Attorney General, the one post she said she would accept.

In 1978, downplaying reports about her poor health, Jordan declined to run for what would have been certain re–election to a fourth term, citing her “internal compass,” which she said was pointing her “away from demands that are all consuming.”13 She also said she wanted to work more directly on behalf of her fellow Texans. Jordan was appointed the Lyndon Johnson Chair in National Policy at the LBJ School of Public Affairs at the University of Texas in Austin, where she taught until the early 1990s. She continued to lecture widely on national affairs. In 1988 and 1992, she delivered speeches at the Democratic National Convention. Her 1992 keynote address was delivered from a wheelchair while she was in the midst of a lengthy battle with multiple sclerosis. In 1994, President William J. (Bill) Clinton appointed her to lead the Commission on Immigration Reform, a bipartisan group that delivered its findings in September of that year. Jordan received nearly two dozen honorary degrees and, in 1990, was named to the National Women’s Hall of Fame in Seneca, New York. She never married and carefully guarded her private life. Jordan died in Austin, Texas, on January 17, 1996, from pneumonia that was a complication of leukemia.

Palm oil is literally everywhere – in our foods, cosmetics, cleaning products and fuels. It’s a source of huge profits for multinational corporations, while at the same time destroying the livelihoods of smallholders. Displacement of indigenous peoples, deforestation and loss of biodiversity are all consequences of our palm oil consumption. How could it come to this? And what can we do in everyday life to protect people and nature?

Palm oil is literally everywhere – in our foods, cosmetics, cleaning products and fuels. It’s a source of huge profits for multinational corporations, while at the same time destroying the livelihoods of smallholders. Displacement of indigenous peoples, deforestation and loss of biodiversity are all consequences of our palm oil consumption. How could it come to this? And what can we do in everyday life to protect people and nature?

You must be logged in to post a comment.