| Lonnie Bunch, museum director, historian, lecturer, and author, is proud to present A Page from Our American Story, a regular on-line series for Museum supporters. It will showcase individuals and events in the African American experience, placing these stories in the context of a larger story — our American story.

A Page From Our American Story

Freddie Stowers, the grandson of a South Carolina slave, holds a unique spot in America’s pantheon of war heroes — as the only African American awarded the Medal of Honor for service in World War I. Stowers’ story, however, must be told in two parts. The first part of the story is his act of heroism in 1918; the second part is that it took more than 72 years before Stowers finally received the recognition he was due. The United States was the last major combatant to enter World War I, the “war to end all wars.” The conflict began in Europe in 1914, but in the U.S., isolationist sentiments were strong resulting in a foreign policy of non-intervention. However, in April 1917, after a German U-boat sank the British ship Lusitania, killing 128 Americans on board, President Woodrow Wilson asked Congress to declare war on Germany. Three months later, on July 3, 1917, American troops landed in France. Corporal Freddie Stowers came to France as part of the all-black Company C, 371st Regiment, 93rd Division that deployed in September, 1918. His service in France was short but courageous and memorable. More than 50 years after the Civil War, America’s military was still segregated. The French, however, had no such rules, and Stowers and Company C were sent to the front lines to serve alongside French troops. On September 28, just days after arriving in France, Stowers’ company was in the midst of an attack on Hill 188, Champagne Marne Sector, France, when enemy forces appeared to be giving up. According to the War Department, German soldiers emerged from their trenches waving a white flag, arms in the air — military actions that signal surrender. It was a ruse, however. As Americans, including Cpl. Stowers, went to capture the “surrendering” Germans, another wave of the enemy arose and opened fire. Very quickly, Company C’s lieutenant and non-commissioned officers were killed in the fight. This left the 21-year-old Stowers in command. Without hesitation, he implored his men to advance on the Germans. Stowers would be mortally shot during the exchange. Wounded and dying, Stowers continued to fight on, inspiring his men to push the enemy back. With Stowers leading the counter-attack, Americans took out an enemy machine gun position and went on to capture Hill 188. Following the battle, Stowers’ commanding officer nominated him for the Medal of Honor, but the nomination was never processed. The Pentagon said the paperwork was misplaced. Some raise the possibility that the nomination wasn’t misplaced at all, but deliberately lost. They point to the fact that American troops were segregated and suggest that racial bias in the military might be the reason for Stowers’ missing paperwork. The final part of Freddie Stowers’ story begins in 1990. As the Department of Defense began to modernize its data systems, it ordered a review of all battlefield medal nominations. When Stowers’ recommendation was found, the Pentagon quickly took action to give the corporal the long overdue recognition and honor he deserved.

On April 24, 1991, more than 72 years after Stowers made the ultimate sacrifice for his nation, his sisters Georgiana Palmer and Mary Bowens, 88- and 77-years-old at the time, were presented his Medal of Honor by President George H. W. Bush. Long before Stowers was honored by his nation, he, along with other members of Company C, received recognition from the French government: “For extraordinary heroism under fire.” Stowers and his unit received the Croix de Guerre – the French War Cross — the highest military medal France awards to allied soldiers. Prior to World War I, 49 African Americans had been awarded the Medal of Honor, including 25 men who fought for the Union in the Civil War. There were 119 Medals of Honor recipients in World War I, with Stowers being the only African American. His long overdue recognition in 1991 is a small but important sign of the progress we as a nation have made.

P.S. We can only reach our $250 million goal with your help. I hope you will consider making a donation or becoming a Charter Member today. |

||||

| The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the newest member of the Smithsonian Institution’s family of extraordinary museums.

The museum will be far more than a collection of objects. The Museum will be a powerful, positive force in the national discussion about race and the important role African Americans have played in the American story — a museum that will make all Americans proud. |

Category Archives: ~ Culture & History

1963~ In memory … Medgar Evers &Myrlie living Black History

Medgar and Myrlie

Medgar and Myrlie Evers are widely regarded as two of the greatest leaders of the civil rights movement. Medgar Evers was a pioneering visionary for civil rights in the 1950s and early 1960s in Mississippi. From the beginning, Myrlie Evers worked alongside her husband, Medgar. In the years following his assassination, she continued the pioneering work they had begun together. In 1998, she founded the Medgar Evers Institute, with the initial goal of preserving and advancing the legacy of Medgar Evers’ life’s work. Anticipating the commemoration of the anniversary of the assassination of Medgar Evers and recognizing the international leadership role of Myrlie Evers, the Institute’s board of directors changed the organization’s name to the Medgar and Myrlie Evers Institute.

Still I Rise – Poem by Maya Angelou

Born April 4, 1928 – May 28, 2014

You may write me down in history

With your bitter, twisted lies,

You may tread me in

the very dirt

But still, like dust, I’ll rise.

Does my sassiness upset you?

Why are you beset with gloom?

‘Cause I walk like I’ve got oil wells

Pumping in my living room.

Just like moons and like suns,

With the certainty of tides,

Just like hopes springing high,

Still, I’ll rise.

Did you want to see me broken?

Bowed head and lowered eyes?

Shoulders falling down like teardrops.

Weakened by my soulful cries.

Does my haughtiness offend you?

Don’t you take it awful hard

‘Cause I laugh like I’ve got gold mines

Diggin’ in my own back yard.

You may shoot me with your words,

You may cut me with your eyes,

You may kill me with your hatefulness,

But still, like air, I’ll rise.

Does my sexiness upset you?

Does it come as a surprise

That I dance like I’ve got diamonds

At the meeting of my thighs?

Out of the huts of history’s shame

I rise

Up from a past, that’s rooted in pain

I rise

I’m a black ocean, leaping and wide,

Welling and swelling I bear in the tide.

Leaving behind nights of terror and fear

I rise

Into a daybreak that’s wondrously clear

I rise

Bringing the gifts that my ancestors gave,

I am the dream and the hope of the slave.

I rise

I rise

I rise.

21st Century … Colonialism

Residual Colonialism In The 21St Century …

The 21st century deserves better. More importantly, the nearly 2 million people still living under colonial rule deserve better.

- Article

- definitely a repost

-

2012•05•29

John Quintero

Photo: DB King

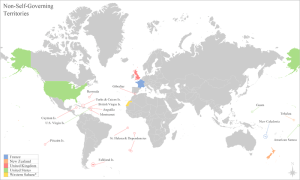

Photo: DB KingThough colonialism is generally considered to be a relic of the past, nearly 2 million people in 16 “non-self-governing territories” across the globe still live under virtual colonial rule. In recognition of the United Nations International Week of Solidarity with the Peoples of Non-Self-Governing Territories (25–31 May), we present this analysis of “residual colonialism in the 21st century”.

♦ ♦ ♦

In 2009, the Government of the United Kingdom (UK) suspended parts of the Constitution of the Turks and Caicos Islands (TCI), a British Overseas Territory, in response to allegations of systemic corruption in the territory. Direct rule from London was imposed over the democratically elected local government. This unilateral, top-down action removed the constitutional right to trial by jury, suspended the ministerial government and the House of Assembly, and charged a UK-appointed Governor with the administration of the islands.

A tentative period for elections has been given (fall 2012 at the earliest), but this is subject to the deliberation of the British government and tied to a series of specific milestones that must be met. These announcements provoked protests and demonstrations by the islanders. The suspension of the TCI government over corruption allegations seems to run contrary to the way in which financial and governance crises are handled around the world, including in the UK itself. Scandals are part of political life, but constitutions are not suspended nor are democratically elected governments and institutions disbanded.

How is it that these events have occurred in a world based on a system of supposedly equal sovereign states? The answer lies in the little known fact that colonial structures continue to exist even today in some parts of the world.

Continuing colonialism

The wave of decolonization that swept around the world in the latter half of the 20th century was once heralded as one of the great liberating movements in history. Yet, few seem to realize that colonialism is still with us. As of 2012, 16 territories are deemed still to be under colonial rule and are labeled by the United Nations as “non-self-governing territories (NSGTs)” — areas in which the population has not yet attained a full measure of self-government.

The 16 NSGTs, home to nearly 2 million people, are spread across the globe. They remain under the tutelage of former colonial powers (currently referred to as “administering powers”), such as the UK, the USA and France.

Most of the NSGTs feature as only small dots on the world map but are in fact prominent players on the world stage. Some act as the world’s leading financial centres, with GDP per capita amongst the world’s top 10 (e.g., the Cayman Islands and Bermuda), some constitute vital bastions for regional security (e.g., Guam), and there are those whose geographical location has made them prone to diplomatic disputes (e.g., Gibraltar and the Falklands/Malvinas).

A UN committee on decolonization does exist (Special Committee of 24 on Decolonization), under the purview of the Fourth Committee of the United Nations General Assembly (Special Political and Decolonization Committee). Its mission is to oversee the implementation of the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (14 December 1960).

The world underwent a political renovation following the formation of the United Nations in 1945, and the number of sovereign UN Member States has skyrocketed from the original 51 to 193. However, the 50-plus years since the founding of the United Nations have proved to be insufficient to eradicate a centuries-old structure of dominance. This is in spite of the advancement of legal systems based on the notions of the sovereign equality of states and human rights prevalent in the contemporary world.

Decolonization, as bluntly put by UN Secretary General Ban Ki-moon, remains an unfinished business; an unfinished process that has been with the international community for too long. In solidarity with the peoples of the NSGTs, the present decade (2010-2020) has been declared the Third International Decade for the Eradication of Colonialism (as the past two decades have proved inadequate to ensure the disappearance of such an archaic concept).

Independence is not the only option

The doctrine of self-determination and political equality has prevailed as the guiding principle for decolonization ever since the inception of the United Nations. Much progress has been achieved and political autonomy for many former dependent states (micro-states, even) has been realized, but the decolonization process remains stalled. No territory has achieved self-government since East Timor (now Timor-Leste) won full independence from Indonesia in 2002.

The many achievements of decolonization by the United Nations cannot be considered truly global while some peoples continue to live under colonial rule. Administering states such as the UK and France continue to exercise top-down authority through modernized dependency governance models that, while perhaps ensuring sustained economic progress, create a democratic deficit and political vulnerability based on unequal status.

The decolonization agenda championed by the United Nations is not based exclusively on independence. There are three other ways in which an NSGT can exercise self-determination and reach a full measure of self-government (all of them equally legitimate): integration within the administering power, free association with the administering power, or some other mutually agreed upon option for self-rule.

The current impasse is due, in part, to the denial by the administering states of these options, but also to a lack of public awareness on the part of the peoples of the NSGTs that they are entitled to freely determine their territory’s political status in accordance with the options presented to them by the United Nations. It is the exercise of the human right of self-determination, rather than independence per se, that the United Nations has continued to push for.

The framework against colonialism

The framework against colonialismInternational law provides a particularly effective conceptual framework from which to criticize these complex dependency arrangements. In the UN Charter, not only Articles 1 and 55 maintain that one of its fundamental purposes and principles is “to develop friendly relations among nations based on respect for the principle of equal rights and self-determination of peoples”. A further three chapters of the Charter are devoted to the dependent territories, namely Chapter XI (Declaration regarding Non-Self-Governing Territories), Chapter XII (International Trusteeship System) and Chapter XIII (The Trusteeship Council).

Core human rights conventions, such as the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights (ICCPR) and the International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights (ICESCR) both affirm the right of self-determination and that the states parties to the covenants have the responsibility to promote the realization of self-determination, in conformity with the provisions of the Charter of the United Nations. Colonialism has been formally delegitimized as an acceptable international practice, as per the Declaration on the Granting of Independence to Colonial Countries and Peoples (General Assembly Resolution 1514 [XV]) in 1960 and a companion resolution defining the three legitimate models of political equality (General Assembly Resolution 1541 [XV]). Further resolutions, for example, established permanent sovereignty over natural resources (General Assembly Resolution 1803 [XVII]).

In October 1970, UN General Assembly Resolution 2621 (XXV) declared that the further continuation of colonialism in all its forms and manifestations is a crime, and in 1977 General Assembly Resolution 32/14 reaffirmed the legitimacy of the struggle of peoples for independence, territorial integrity, national unity and liberation from colonial and foreign domination and alien subjugation by all available means, including armed struggle.

The road ahead

Colonialism made the political world map look much as it does today, drawing up borders with no regard for local sensibilities and realities. It negated or purposefully misconceived the cultural, economic, political and social conditions under which the colonized led their lives. In the process, colonial powers imposed inappropriate identities on the people they ruled, crippling peoples’ self-esteem, thus diminishing their self-efficacy and potentially stunting their long-term social development.

Given the modern emphasis on the equality of states and inalienable nature of their sovereignty, many people do not realize that these non-self-governing structures still exist. Thus, the world has closed its eyes to continuing colonial dependence.

World media has the potential to play a pivotal role in advancing decolonization by exposing developments that infringe on the exercise of the right of self-determination and that worsen the political vulnerability of the NSGTs. The issue at hand is not that colonialism does not exist in today’s world because the populations of these territories overwhelmingly do not define these territories as colonies. Rather, it is that these populations have not been provided with an opportunity to decide on a legitimate political status through popular consultation in the form of an acceptable act of self-determination. Once this is made sufficiently clear, media coverage and overview can be expected.

In light of the disbandment of an overseas democratically elected government in TCI, the international community, the public in general and the peoples of the NGSTs alike have been reminded that the UN agenda on colonialism is very much relevant and crucial — -not only for the protection of fundamental human rights, but to democratic governance and an international order principled upon the notions of sovereignty and the equality of states.

One of the greatest and most visible achievements of the United Nations has been to pursue the decolonization of the colonized world. However, a successful end to this process cannot be based on simply removing territories from the UN list of NSGTs (de-listing), but rather on the actual achievement of full self-government.

De-listing cannot be perceived as the goal, but rather as a secondary product resulting from clear indicators of self-government, political equality vis-à-vis the administering state, and the promotion and support of genuine political education programmes that allow the populace of those territories to freely choose their status and their future. Not doing so would result in stymieing the legitimate aspirations of peoples whose human rights the United Nations was created to protect.

Colonialism is a concept of an exploitative past that runs counter to the principles of sovereign equality on which the United Nations is grounded. As commonly expressed in General Assembly debates, colonialism is anachronistic, archaic, and outmoded; it contravenes the fundamental tenets of democracy, freedom, human dignity and human rights.

The 21st century deserves better. Most importantly, the nearly 2 million people still living under colonial rule deserve better.

Black History Month

In memory of 1/22 ~ Stories That Show What Abortion Was Like Before Roe v. Wade -a reminder, a repost

January 19, 2016 by Stephanie Hallett

As the anniversary of Roe v. Wade approaches on Jan. 22—and with the Supreme Court set to revisit women’s fundamental right to access abortion in the Whole Woman’s Health v. Cole case, the most serious threat to abortion since 1992—the Ms. Blog decided to look back at the realities of illegal abortion pre-Roe, and for women today who lack access to proper care.

As part of our #WeWontGoBack campaign, Ms. Blog readers are sharing their own stories, or the stories of friends and family members who have resorted to illegal abortions because they had no choice. Use the hashtag to share your story on social media.

Below, read pre-Roe abortion stories collected from the Ms. Facebook page.

“In 9th grade a good friend became pregnant by our AAU coach. He threatened to kill her if she told how she became pregnant. Her parents were divorced and her mother had committed suicide a few weeks prior. She borrowed money from everyone and wrote a check on [her] dad’s account to go to [the] local abortionist. She died in [the] girls bathroom a week later. … She was a very talented artist and composed music. I had known her since third grade and even now, at 62, can hear her laughter and have a caricature of myself she drew. She had to be buried in a different cementary as was Catholic raised, as did her mom. After her death a group told the coach to quit or we would tell. We were 14-year-old kids doing the best we could for our friend. … She was just a baby herself.” — Evelyn H.

“When I was in a Midwest high school, we pooled our babysitting money to help our 16-year-old friend fly to Mexico, alone, for an abortion. Her parents thought she was staying at a friend’s home overnight. Imagine. I am 64. Never again—not going back.” — Bonnie B.

“My mom had one in Tijuana in the late 1960s. She told me she remembers watching the doctor use fire to sterilize the tools. She was OK, but terrified. She had given up a child for adoption a few years prior and couldn’t face that loss again. … I need to get the full story from her soon. I was afraid to ask for more details. It seemed like something she had kept hidden for so long. She only shared this with me when I was in my late 20s. Abortion must remain a safe and legal option.” — Jena G.

“I had a roommate in Madison, Wisconsin who became pregnant and, because in 1969 you couldn’t get an abortion in Wisconsin, the four roommates chipped in to buy her a plane ticket to NYC to have the abortion. She came home in fine shape but it was traumatic for her not to have a regional option and not having the funds as a college student to pay for it. So when I read about the closing of Planned Parenthood clinics so that underserved women don’t have regional options even for breast exams or Pap smears it is infuriating!” — Susan A.K.

“My submission is very short. It is about my Mother, b. 1924, d. 1971.

She was found in a pool of blood on her cold white tile bathroom floor. Her mother found her. She was discovered, [she] did not die. Later, she had my sister and me. After her suicide at age 46, her mother told [me] about finding her daughter unconscious in a pool of blood.” — Carol F.

“In 1932 at the height of the Great Depression, my grandmother had one little boy and was five months pregnant with her second child. She was a lifelong, devout Catholic. My grandfather just came home to their tiny-two room apartment and informed her that he was leaving her for another woman. She had no job and was about to be evicted from her apartment. She was desperate, terrified and alone. A week after my grandfather left, she found a back-alley abortionist who performed [the] abortion and she very nearly bled to death. … [Then] she returned home and delivered a ‘stillborn’ (or so her parents thought) baby boy. She developed peritonitis and lapsed into a weeklong coma. When she regained consciousness and realized what she had done, she cried non-stop for two months. I was the only person she ever told; she told me that her grief and sorrow was so intense that she feared dying as she was terrified of having to face the child she aborted. She lived to be 102 and never once allowed herself forgiveness.” — Patricia H.

“My mom spoke of aunts and other beloved female family members who could not afford and/or could not handle another pregnancy and child. All that was available to them was ‘kitchen table’ abortions done in secret with a coat hanger. The pregnancy was aborted, but these women died horrible deaths from peritonitis due to internal punctures and infections. They felt as though they had no choice and were desperate not to have more children. My mom was haunted by their stories and the fact they felt so trapped. It was such a loss for her and the family to lose these lively, strong women. This was in the 1930s and ’40s.” — Jayne B.

“I’m a 62-year-old man but I know that my single mother had an illegal abortion in her teens, before I was born, that almost killed her. She couldn’t stop bleeding and couldn’t go to the hospital without facing criminal charges. All she could do was wait it out in a hotel room. Apparently, her boyfriend collected newspapers for her to sit on to collect the blood.” — Wm P.

Photo via Flickr user Kool Cats Photography licensed under Creative Commons 2.0

You must be logged in to post a comment.