Source: on this day.com

Source: on this day.com

CONTRIBUTED BY: WILL MACK

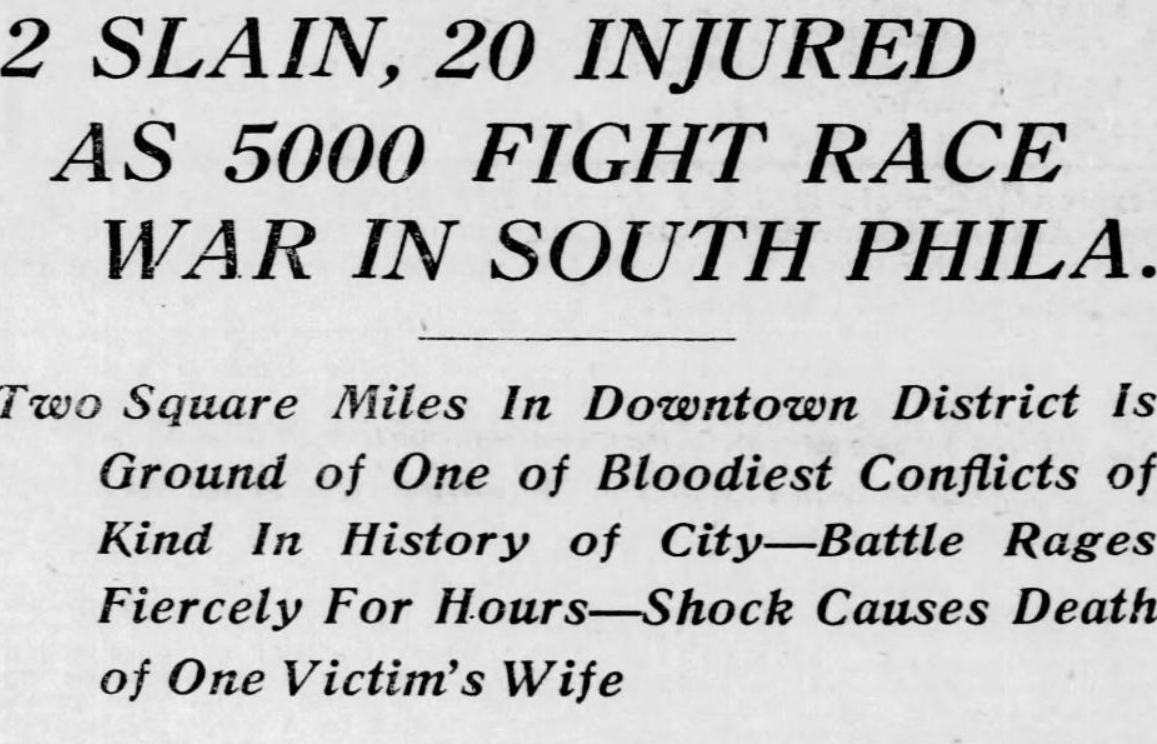

Newspaper clipping of The Philadelphia Inquirer in the aftermath of the 1918 Philadelphia Race Riot

The 1918 Race Riot in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania began on July 26, 1918, two days after an African American woman, Adella Bond, moved into her new home in a primarily white area of South Philadelphia. On the evening of the July 26, a large crowd of white people gathered outside Bond’s home. As tensions rose within the crowd, someone threw a rock through Bond’s window. Bond responded by firing a pistol into the air to call for help from the police but she unintentionally hit and injured Joseph Kelly, one of men in the crowd outside. Rioting began in earnest with Kelly’s shooting and several people were arrested when the police arrived.

Rioting continued on Saturday, July 27 when a group of white men accused an African American man, William Box, of theft. Attempting to defend himself, Box cut one of his attackers on the arm. His self-defense enraged the mob, who attacked him and attempted to lynch him, when police arrived and arrested Box for assault.

For the complete article, blackpast.org

The act:

Initially each of the three service secretaries maintained quasi-cabinet status, but the act was amended on August 10, 1949 to formalize their subordination to the secretary of defense. At the same time the NME was renamed the Department of Defense.

In the intelligence field, the act ratified President Truman’s creation (in 1946) of the post of Director of Central Intelligence (DCI), and transformed the Central Intelligence Group into the statutory Central Intelligence Agency (CIA), the nation’s first peacetime intelligence agency.

Most of these provisions prompted sharp debates in the Executive Branch and Congress. Several compromises were struck in order for the act to win passage. These compromises would have far-reaching implications for the Intelligence Community.

President Truman’s main goal in guiding this legislation through Congress was to modernize the nation’s “antiquated defense setup” by unifying the armed services under a civilian chief. Intelligence reform was a secondary goal, and the White House kept the bill’s passages on intelligence as brief as possible to ensure that its details did not hamper prospects for military unification. This tactic almost backfired.

When the president sent his bill forward in February 1947, the brevity of its intelligence provisions caused Congressional scrutiny. More than a few members of Congress read the bill with concerns about its proposed concentration of military power.

They also eventually debated almost every word of its bill’s intelligence section. Some members argued that the DCI and the new CIA could become a menace to civil liberties–an “American Gestapo.” Administration witnesses alleviated this concern by reminding Congress that the Agency’s authorized mission would be foreign intelligence.

When lawmakers finished editing the section on intelligence, however, the language managed to summarize and ratify most of the crucial arrangements already made by the Truman administration. The National Security Act would:

The legislation gave America something new; no other nation had structured its foreign intelligence establishment in quite the same way.

The CIA would be an independent, central agency, overseeing strategic analysis and coordinating clandestine activities abroad. It would not be a controlling agency. The CIA would both rival and complement the efforts of the departmental intelligence organizations. This prescription of coordination without control guaranteed competition as the CIA and the departmental agencies pursued common targets, but it also fostered a healthy exchange of views and abilities.

What the act did not do, however, was almost as important as what it did. It helped ensure that American intelligence remained a loose confederation of agencies lacking strong direction from either civilian or military decisionmakers. President Truman had endorsed the Army and Navy view that “every department required its own intelligence.” The National Security Act left this concession in tact. Only later would the Defense Intelligence Agency be created to coordinate military intelligence.

The act also made a crucial concession to members concerned about threats to civil liberties. It drew a bright line between foreign and domestic intelligence and assigning these realms, in effect, to the CIA and the Federal Bureau of Investigation, respectively. The CIA, furthermore, would have no “police, subpoena, or law enforcement powers,” according to the act.

The importance of the National Security Act cannot be overstated. It was a central document in U.S. Cold War policy and reflected the nation’s acceptance of its position as a world leader.

You must be logged in to post a comment.