The World Premiere: In 2010 at Sundance Film Festival, US

A Documentary Competition

Award-winning filmmaker Stanley Nelson (Wounded Knee, Jonestown: The Life and Death of Peoples Temple, The Murder of Emmett Till) returns to the Sundance Film Festival with his latest documentary FREEDOM RIDERS, the powerful, harrowing and ultimately inspirational story of six months in 1961 that changed America forever. From May until November 1961, more than 400 black and white Americans risked their lives—and many endured savage beatings and imprisonment—for simply traveling together on buses and trains as they journeyed through the Deep South. Deliberately violating Jim Crow laws, the Freedom Riders’ belief in non-violent activism was sorely tested as mob violence and bitter racism greeted them along the way.

FREEDOM RIDERS features testimony from a fascinating cast of central characters: the Riders themselves, state and federal government officials, and journalists who witnessed the rides firsthand.

“I got up one morning in May and I said to my folks at home, I won’t be back today because I’m a Freedom Rider. It was like a wave or a wind that you didn’t know where it was coming from or where it was going, but you knew you were supposed to be there.” — Pauline Knight-Ofuso, Freedom Rider

Despite two earlier Supreme Court decisions that mandated the desegregation of interstate travel facilities, black Americans in 1961 continued to endure hostility and racism while traveling through the South. The newly inaugurated Kennedy administration, embroiled in the Cold War and worried about the nuclear threat, did little to address domestic Civil Rights.

“It became clear that the Civil Rights leaders had to do something desperate, something dramatic to get Kennedy’s attention. That was the idea behind the Freedom Rides—to dare the federal government to do what it was supposed to do, and see if their constitutional rights would be protected by the Kennedy administration,” explains Raymond Arsenault, author of Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice, on which the film is partially based.

Organized by the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE), the self-proclaimed “Freedom Riders” came from all strata of American society—black and white, young and old, male and female, Northern and Southern. They embarked on the Rides knowing the danger but firmly committed to the ideals of non-violent protest, aware that their actions could provoke a savage response but willing to put their lives on the line for the cause of justice.

Each time the Freedom Rides met violence and the campaign seemed doomed, new ways were found to sustain and even expand the movement. After Klansmen in Alabama set fire to the original Freedom Ride bus, student activists from Nashville organized a ride of their own. “We were past fear. If we were going to die, we were gonna die, but we can’t stop,” recalls Rider Joan Trumpauer-Mulholland. “If one person falls, others take their place.”

Later, Mississippi officials locked up more than 300 Riders in the notorious Parchman State Penitentiary. Rather than weaken the Riders’ resolve, the move only strengthened their determination. None of the obstacles placed in their path would weaken their commitment.

The Riders’ journey was front-page news and the world was watching. After nearly five months of fighting, the federal government capitulated. On September 22, the Interstate Commerce Commission issued its order to end the segregation in bus and rail stations that had been in place for generations. “This was the first unambiguous victory in the long history of the Civil Rights Movement. It finally said, ‘We can do this.’ And it raised expectations across the board for greater victories in the future,” says Arsenault.

“The people that took a seat on these buses, that went to jail in Jackson, that went to Parchman, they were never the same. We had moments there to learn, to teach each other the way of nonviolence, the way of love, the way of peace. The Freedom Ride created an unbelievable sense: Yes, we will make it. Yes, we will survive. And that nothing, but nothing, was going to stop this movement,” recalls Congressman John Lewis, one of the original Riders.

Says Stanley Nelson, “The lesson of the Freedom Rides is that great change can come from a few small steps taken by courageous people. And that sometimes to do any great thing, it’s important that we step out alone.”

CREDITS

A Stanley Nelson Film

A Firelight Media Production for AMERICAN EXPERIENCE

Produced, Written and Directed by

Stanley Nelson

Produced by

Laurens Grant

Edited by

Lewis Erskine, Aljernon Tunsil

Archival Producer

Lewanne Jones

Associate Producer

Stacey HolmanDirector of Photography

Robert Shepard

Composer

Tom Phillips

Music Supervisor

Rena Kosersky

Based in part on the book Freedom Riders by

Raymond Arsenault

AMERICAN EXPERIENCE is a production of WGBH Boston.

Senior producer

Sharon Grimberg

Executive producer

Mark Samels

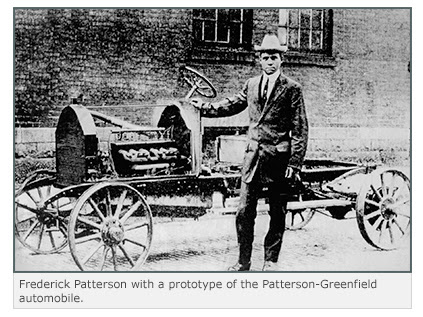

At first, the company offered repair and restoration services for the “horseless carriages” that were beginning to proliferate on the streets of Greenfield. No doubt this gave workers the opportunity to gain some hands-on knowledge about these noisy, smoky and often unreliable contraptions. Like his father, Frederick was a strong believer in advertising and placed his first ad for auto repair services in the local paper in 1913. Initially, the work mostly involved repainting bodies and reupholstering interiors, but as the shop gained more experience with engines and drivetrains, they began to offer sophisticated upgrades and improvements to electrical and mechanical systems as well.

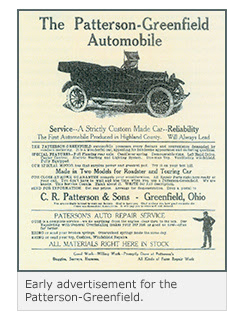

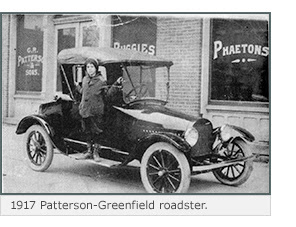

At first, the company offered repair and restoration services for the “horseless carriages” that were beginning to proliferate on the streets of Greenfield. No doubt this gave workers the opportunity to gain some hands-on knowledge about these noisy, smoky and often unreliable contraptions. Like his father, Frederick was a strong believer in advertising and placed his first ad for auto repair services in the local paper in 1913. Initially, the work mostly involved repainting bodies and reupholstering interiors, but as the shop gained more experience with engines and drivetrains, they began to offer sophisticated upgrades and improvements to electrical and mechanical systems as well. Orders began to come in, and C.R. Patterson & Sons officially entered the ranks of American auto manufacturers. Over the years, several models of coupes and sedans were offered, including a stylish “Red Devil” speedster. Ads featured the car’s 30hp Continental 4-cylinder engine, full floating rear axle, cantilever springs, electric starting and lighting, and a split windshield for ventilation. The build quality of the Patterson-Greenfield automobile was as highly regarded as it had been with their carriages.

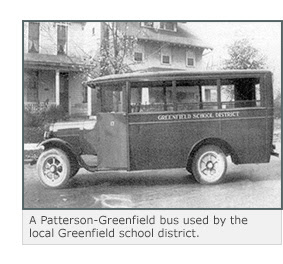

Orders began to come in, and C.R. Patterson & Sons officially entered the ranks of American auto manufacturers. Over the years, several models of coupes and sedans were offered, including a stylish “Red Devil” speedster. Ads featured the car’s 30hp Continental 4-cylinder engine, full floating rear axle, cantilever springs, electric starting and lighting, and a split windshield for ventilation. The build quality of the Patterson-Greenfield automobile was as highly regarded as it had been with their carriages. In 1918, having built by some estimates between 30 and 150 vehicles, C.R. Patterson & Sons halted auto production and concentrated once again on the repair side of the business. But they weren’t done yet. In the 1920s, the company began building truck and bus bodies to be fitted on chassis made by other manufacturers. It was in a sense a return to their original skills in building carriage bodies without engines and drivetrains and, for a period of time, the company was quite profitable. Then in 1929, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression set in. As with many small businesses, sales dried up and loans were hard to obtain. The company, now run by the sons of Frederick Patterson, soldiered on until 1939 when, after 74 years, C.R. Patterson & Sons closed its doors forever.

In 1918, having built by some estimates between 30 and 150 vehicles, C.R. Patterson & Sons halted auto production and concentrated once again on the repair side of the business. But they weren’t done yet. In the 1920s, the company began building truck and bus bodies to be fitted on chassis made by other manufacturers. It was in a sense a return to their original skills in building carriage bodies without engines and drivetrains and, for a period of time, the company was quite profitable. Then in 1929, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression set in. As with many small businesses, sales dried up and loans were hard to obtain. The company, now run by the sons of Frederick Patterson, soldiered on until 1939 when, after 74 years, C.R. Patterson & Sons closed its doors forever.

You must be logged in to post a comment.