|

‘Twelve Years a Slave‘:

5 Facts on the Real Solomon Northup

|

Daily Archives: 02/07/2021

The Only African American Automobile Company! ~~ Lonnie G. Bunch at The NMAAHC- in memory of Black History

| Lonnie Bunch, museum director, historian, lecturer, and author, is proud to present A Page from Our American Story, a regular on-line series for Museum supporters. It will showcase individuals and events in the African American experience, placing these stories in the context of a larger story — our American story. | ||||

| A Page From Our American Story | ||||

At the dawn of the Automobile Age in the early 20th century, hundreds of small auto companies sprouted up across America as entrepreneurs recognized that society was transitioning from horse-drawn carriages to transportation powered by the internal combustion engine. Some of these early companies grew to become giants that are still with us today, such as Ford and Chevrolet. Many others remained small, struggling to compete against the assembly lines of the larger manufacturers.One such company was C.R. Patterson & Sons of Greenfield, Ohio, makers of the Patterson-Greenfield automobile from 1915 to 1918. Though its name is little recognized today, there is in fact a very important reason to ensure that it is not lost to history: it was, and remains to this day,the only African American owned and operated automobile company.

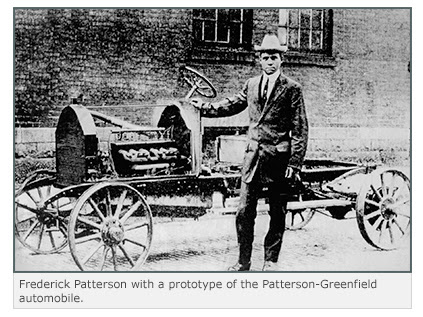

Charles Richard Patterson was born into slavery on a Virginia plantation in 1833. Not much is known about his life on the plantation, and historians have to sift through conflicting reports about how he came to settle in Greenfield, Ohio, a town with strong abolitionist sympathies. Some say his family arrived in the 1840s, possibly after purchasing their freedom; others suggest Patterson alone escaped in 1861. In any case, he learned the skills of the blacksmith and found work in the carriage-making trade, where he developed a reputation for building a high quality product. In 1873, he formed a business partnership with another carriage maker in town, J.P. Lowe, who was white, and eventually became sole proprietor of the renamed C.R. Patterson & Sons in 1893. It was a successful business employing an integrated workforce of 35-50 by the turn of the century, and Charles Patterson became a prominent and respected citizen in Greenfield. His catalog listed some 28 models, from simple open buggies to larger and more expensive closed carriages for doctors and other professionals. When Patterson died in 1910, the business passed to his son Frederick, who was already something of a pioneer. He was college-educated and was the first black athlete to play football for Ohio State University. He was also an early member and vice president of the National Negro Business League founded by Booker T. Washington. Now, as owner and operator of the enterprise his father started, Frederick Patterson began to see the handwriting on the wall: the days of carriages and horse-drawn buggies were nearing an end.

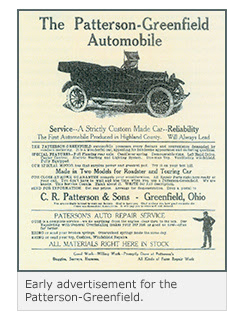

This valuable experience allowed C.R. Patterson & Sons to take the next great step in its own story as well as in African American history: in 1915, it announced the availability of the Patterson-Greenfield automobile at a price of $685. From the company’s publicity efforts, it is evident they were bursting with pride: “Our car is made with three distinct purposes in mind. First — It is not intended for a large car. It is designed to take the place originally held by the family surrey. It is a 5-passenger vehicle, ample and luxurious. Second — It is intended to meet the requirements of that class of users, who, though perfectly able to spend twice the amount, yet feel that a machine should not engross a disproportionate share of expenditure, and especially it should not do so to the exclusion of proper provisions for home and home comfort, and the travel of varied other pleasurable and beneficial entertainment. It is a sensibly priced car. Third — It is intended to carry with it (and it does so to perfection) every conceivable convenience and every luxury known to car manufacture. There is absolutely nothing shoddy about it. Nothing skimp and stingy.”

The initial hope and optimism, however, proved to be fairly short-lived. In an age of increased mechanization and production lines, small independent shops featuring hand-built, high quality products weren’t able to scale up production or compete on price against the rapidly growing car companies out of Detroit. In small quantities, parts and supplies were expensive and hard to come by when major manufacturers were buying them by the trainload at greatly reduced costs. Plus, the labor hours per car were much higher than that of assembly line manufacturers. As a result, the profit margin on each Patterson-Greenfield was low.

Sadly, no Patterson-Greenfield automobiles are known to survive today. But we should not let that dim the fact that two great entrepreneurs, Charles Richard Patterson and his son Frederick Patterson built and sustained a business that lasted several generations and earned a place not just in African American history, but in automotive history as well.

The National Museum of African American History and Culture is the newest member of the Smithsonian Institution’s family of extraordinary museums. The museum will be far more than a collection of objects. The Museum will be a powerful, positive force in the national discussion about race and the important role African Americans have played in the American story — a museum that will make all Americans proud. P.S. We can only reach our $250 million goal with your help. I hope you will consider making a donation or becoming a Charter Member today. |

||||

U.S. Senate Oath of Office

Oath of Office

I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support and defend the Constitution of the United States against all enemies, foreign and domestic; that I will bear true faith and allegiance to the same; that I take this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion; and that I will well and faithfully discharge the duties of the office on which I am about to enter: So help me God.History of the Oath

At the start of each new Congress, in January of every odd-numbered year, the entire House of Representatives and one-third of the Senate performs a solemn and festive constitutional rite that is as old as the Republic. While the oath-taking dates back to the First Congress in 1789, the current oath is a product of the 1860s, drafted by Civil War-era members of Congress intent on ensnaring traitors.

The Constitution contains an oath of office only for the president. For other officials, including members of Congress, that document specifies only that they “shall be bound by Oath or Affirmation to support this constitution.” In 1789, the First Congress reworked this requirement into a simple fourteen-word oath: “I do solemnly swear (or affirm) that I will support the Constitution of the United States.”

For nearly three-quarters of a century, that oath served nicely, although to the modern ear it sounds woefully incomplete. Missing are the soaring references to bearing “true faith and allegiance;” to taking “this obligation freely, without any mental reservation or purpose of evasion;” and to “well and faithfully” discharging the duties of the office.

The outbreak of the Civil War quickly transformed the routine act of oath-taking into one of enormous significance. In April of 1861, a time of uncertain and shifting loyalties, President Abraham Lincoln ordered all federal civilian employees within the executive branch to take an expanded oath. When Congress convened for a brief emergency session in July, members echoed the president’s action by enacting legislation requiring employees to take the expanded oath in support of the Union. This oath is the earliest direct predecessor of the modern oath.

When Congress returned for its regular session in December 1861, members who believed that the Union had as much to fear from northern traitors as southern soldiers again revised the oath, adding a new first section known as the “Ironclad Test Oath.” The war-inspired Test Oath, signed into law on July 2, 1862, required “every person elected or appointed to any office … under the Government of the United States … excepting the President of the United States” to swear or affirm that they had never previously engaged in criminal or disloyal conduct. Those government employees who failed to take the 1862 Test Oath would not receive a salary; those who swore falsely would be prosecuted for perjury and forever denied federal employment.

The 1862 oath’s second section incorporated a more polished and graceful rendering of the hastily drafted 1861 oath. Although Congress did not extend coverage of the Ironclad Test Oath to its own members, many took it voluntarily. Angered by those who refused this symbolic act during a wartime crisis, and determined to prevent the eventual return of prewar southern leaders to positions of power in the national government, congressional hard-liners eventually succeeded by 1864 in making the Test Oath mandatory for all members.

The Senate then revised its rules to require that members not only take the Test Oath orally, but also that they “subscribe” to it by signing a printed copy. This condition reflected a wartime practice in which military and civilian authorities required anyone wishing to do business with the federal government to sign a copy of the Test Oath. The current practice of newly sworn senators signing individual pages in an elegantly bound oath book dates from this period.

As tensions cooled during the decade following the Civil War, Congress enacted private legislation permitting particular former Confederates to take only the second section of the 1862 oath. An 1868 public law prescribed this alternative oath for “any person who has participated in the late rebellion, and from whom all legal disabilities arising therefrom have been removed by act of Congress.” Northerners immediately pointed to the new law’s unfair double standard that required loyal Unionists to take the Test Oath’s harsh first section while permitting ex-Confederates to ignore it. In 1884, a new generation of lawmakers quietly repealed the first section of the Test Oath, leaving intact today’s moving affirmation of constitutional allegiance.Taking the Oath

At the beginning of a new term of office, senators-elect take their oath of office from the presiding officer in an open session of the Senate before they can begin to perform their legislative activities. From the earliest days, the senator-elect—both the freshman and the returning veteran—has been escorted down the aisle by another senator to take the oath from the presiding officer. Customarily, the other senator from the senator-elect’s state performs that ritual. Occasionally, the senator-elect chooses a senator from another state, either because the same-state colleague is absent or because the newly elected senator has sharp political differences with that colleague. Such public displays of these differences do not go unnoticed by journalists.

A ban on photography in the Senate chamber has led senators to devise an alternative way of capturing this highly symbolic moment in their Senate careers. In earlier times, the Vice President invited newly sworn senators and their families into his Capitol office for a reenactment for home-state photographers. Beginning in the late 1970s, following the restoration of the Old Senate Chamber to its appearance at the time it went out of service in 1859, reenactment ceremonies have been held in that deeply historical setting, resplendent in crimson and gold.

Source: senate.gov

At first, the company offered repair and restoration services for the “horseless carriages” that were beginning to proliferate on the streets of Greenfield. No doubt this gave workers the opportunity to gain some hands-on knowledge about these noisy, smoky and often unreliable contraptions. Like his father, Frederick was a strong believer in advertising and placed his first ad for auto repair services in the local paper in 1913. Initially, the work mostly involved repainting bodies and reupholstering interiors, but as the shop gained more experience with engines and drivetrains, they began to offer sophisticated upgrades and improvements to electrical and mechanical systems as well.

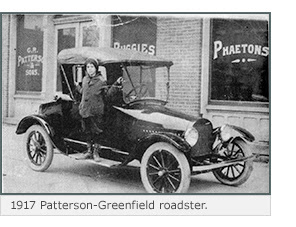

At first, the company offered repair and restoration services for the “horseless carriages” that were beginning to proliferate on the streets of Greenfield. No doubt this gave workers the opportunity to gain some hands-on knowledge about these noisy, smoky and often unreliable contraptions. Like his father, Frederick was a strong believer in advertising and placed his first ad for auto repair services in the local paper in 1913. Initially, the work mostly involved repainting bodies and reupholstering interiors, but as the shop gained more experience with engines and drivetrains, they began to offer sophisticated upgrades and improvements to electrical and mechanical systems as well. Orders began to come in, and C.R. Patterson & Sons officially entered the ranks of American auto manufacturers. Over the years, several models of coupes and sedans were offered, including a stylish “Red Devil” speedster. Ads featured the car’s 30hp Continental 4-cylinder engine, full floating rear axle, cantilever springs, electric starting and lighting, and a split windshield for ventilation. The build quality of the Patterson-Greenfield automobile was as highly regarded as it had been with their carriages.

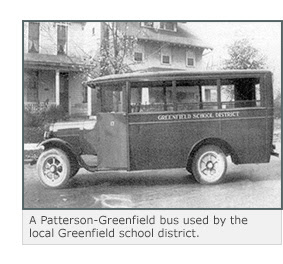

Orders began to come in, and C.R. Patterson & Sons officially entered the ranks of American auto manufacturers. Over the years, several models of coupes and sedans were offered, including a stylish “Red Devil” speedster. Ads featured the car’s 30hp Continental 4-cylinder engine, full floating rear axle, cantilever springs, electric starting and lighting, and a split windshield for ventilation. The build quality of the Patterson-Greenfield automobile was as highly regarded as it had been with their carriages. In 1918, having built by some estimates between 30 and 150 vehicles, C.R. Patterson & Sons halted auto production and concentrated once again on the repair side of the business. But they weren’t done yet. In the 1920s, the company began building truck and bus bodies to be fitted on chassis made by other manufacturers. It was in a sense a return to their original skills in building carriage bodies without engines and drivetrains and, for a period of time, the company was quite profitable. Then in 1929, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression set in. As with many small businesses, sales dried up and loans were hard to obtain. The company, now run by the sons of Frederick Patterson, soldiered on until 1939 when, after 74 years, C.R. Patterson & Sons closed its doors forever.

In 1918, having built by some estimates between 30 and 150 vehicles, C.R. Patterson & Sons halted auto production and concentrated once again on the repair side of the business. But they weren’t done yet. In the 1920s, the company began building truck and bus bodies to be fitted on chassis made by other manufacturers. It was in a sense a return to their original skills in building carriage bodies without engines and drivetrains and, for a period of time, the company was quite profitable. Then in 1929, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression set in. As with many small businesses, sales dried up and loans were hard to obtain. The company, now run by the sons of Frederick Patterson, soldiered on until 1939 when, after 74 years, C.R. Patterson & Sons closed its doors forever.

You must be logged in to post a comment.