by James Baigrie – 2016

pretty sure the list has increased!

A

Aerosol cans: These can usually be recycled with other cans, as long as you pull off the plastic cap and empty the canister completely.

Antiperspirant and deodorant sticks: Many brands have a dial on the bottom that is made of a plastic polymer that’s different from the plastic used for the container, so your center might not be able to recycle the whole thing (look on the bottom to find out). Tom’s of Maine makes a deodorant stick composed solely of plastic No. 5.

B

Backpacks: The American Birding Association accepts donated backpacks, which its scientists use while tracking neotropical birds (americanbirding.org).

Batteries: Recycling batteries keeps hazardous metals out of landfills. Many stores, like RadioShack and Office Depot, accept reusable ones, as does the Rechargeable Battery Recycling Corporation (rbrc.org/call2recycle). Car batteries contain lead and can’t go in landfills, because toxic metals can leach into groundwater, but almost any retailer selling them will also collect and recycle them.

Beach balls: They may be made of plastic, but there aren’t enough beach balls being thrown away to make them a profitable item to recycle. If a beach ball is still usable, donate it to a thrift store or a children’s hospital.

Books: “Hard covers are too rigid to recycle, so we ask people to remove them and recycle just the pages,” says Sarah Kite, recycling manager of the Rhode Island Resource Recovery Corporation, in Johnston. In many areas, paperbacks can be tossed in with other paper.

C

Carpeting (nylon fiber): Go to carpetrecovery.org and click on “What can I do with my old carpet?” to find a carpet-reclamation facility near you, or check with your carpet’s manufacturer. Some carpet makers, like Milliken (millikencarpet.com), Shaw (shawfloors.com), and Flor (flor.com), have recycling programs.

Cars, Jet Skis, boats, trailers, RVs, and motorcycles: Even if these are unusable―totaled, rusted―they still have metal and other components that can be recycled. Call junkyards in your area, or go to junkmycar.com, which will pick up and remove cars, trailers, motorcycles, and other heavy equipment for free.

Cell phones: According to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency, fewer than 20 percent of cell phones are recycled each year, and most people don’t know where to recycle them. The Wireless Foundation refurbishes old phones to give to domestic-violence survivor calltoprotect.org. For information on other cell-phone charities, log on to gowirelessgogreen.org. In some states, like California and New York, retailers must accept and recycle old cell phones at no charge.

How to Recycle Anything

An A-to-Z guide of what can be tossed into which bin.

By Natalie Ermann Russell

Compact fluorescent lightbulbs: CFLs contain mercury and shouldn’t be thrown in the trash. Ikea and the Home Depot operate CFL recycling programs; you can also check with your local hardware store or recycling center to see if it offers recycling services.

Computers: You can return used computers to their manufacturers for recycling (check mygreenelectronics.com for a list of vendors) or donate them to a charitable organization (log on to sharetechnology.org or cristina.org). Nextsteprecycling.org repairs your broken computers and gives them to underfunded schools, needy families, and nonprofits.

Crayons: Send them to the National Crayon Recycle Program (crazycrayons.com, which melts down crayons and reforms them into new ones. Leave the wrappers on: “When you have black, blue, and purple crayons together without wrappers, it’s hard to tell them apart,” says the program’s founder, LuAnn Foty, a.k.a. the Crazy Crayon Lady.

Crocs: The manufacturer recycles used Crocs into new shoes and donates them to underprivileged families. Mail them to: Crocs Recycling West, 3375 Enterprise Avenue, Bloomington CA 92316.

D

DVDs, CDs, and jewel cases: If you want to get rid of that Lionel Richie CD because “Dancing on the Ceiling” doesn’t do it for you anymore, you can swap it for a disc from another music lover at zunafish.com. But if you just want to let it go and not worry about it ending up in a landfill, send it (along with DVDs and jewel cases) to greendisk.com for recycling.

E

Empty metal cans (cleaning products): Cut off the metal ends of cans containing powdered cleansers, such as Ajax and Bon Ami, and put them in with other household metals. (Use care when cutting them.) Recycle the tubes as you would any other cardboard.

Empty metal cans (food products): Many towns recycle food cans. If yours doesn’t, you can find the nearest steel-can recycling spot at recycle-steel.org. Rinse out cans, but don’t worry about removing the labels. “Leaving them on doesn’t do any harm,” says Marti Matsch, the communications director of Eco-Cycle, one of the nation’s oldest and largest recyclers, in Boulder, Colorado. “When the metal is melted,” she says, “the paper burns up. If you want to recycle the label with other paper, that’s great, but it’s not necessary.”

Eyeglasses: Plastic frames can’t be recycled, but metal ones can. Just drop them into the scrap-metal bin. However, given the millions of people who need glasses but can’t afford them, your frames, broken or not, will go to better use if you donate them to neweyesfortheneedy.com (sunglasses and plastic frames in good condition can also be donated). Or drop off old pairs of glasses at LensCrafters, Target Optical, or other participating stores and doctors’ offices, which will send them to onesight.org.

F

Fake plastic credit cards: They’re not recyclable, so you can’t just toss them along with their paper junk-mail solicitations. Remove them first and throw them in the trash.

Film canisters: Check with your local recycling center to find out if it takes gray film-container lids (No. 4) and black bases (No. 2). If not, many photo labs will accept them.

Fire extinguishers: There are two types of extinguishers. For a dry-chemical extinguisher, safely relieve the remaining pressure, remove the head from the container, and place it with your bulk-metal items (check with your local recycler first). Alternatively, call fire-equipment companies and request that they dispose of your extinguisher. Carbon dioxide extinguishers are refillable after each use.

Food processors. Some communities accept small household appliances for recycling―if not in curbside collection, then in drop-off locations. (New York City will even pick up appliances left on the sidewalk.) “If an appliance is more than 50 percent metal, it is recyclable,” says Kathy Dawkins, director of public information for New York City’s Department of Sanitation. Most appliances are about 75 percent steel, according to the Steel Recycling Institute. So unless you know something is mostly plastic, it will probably qualify.

Formal wear: Finally, a use for that mauve prom or bridesmaid dress: Give it to a girl who can’t afford one (go to operationfairydust.org or catherinescloset.org).

G

Gadgets: There are many ways to recycle PDAs, MP3 players, and other devices so that any money earned from the parts goes to worthy causes―a win, win, win scenario (for you, the environment, and charity). Recycleforbreastcancer.org, for example, will send you prepaid shipping labels, recycle your gadgets, then donate the proceeds to breast cancer charities.

Glue: Many schools have recycling programs for empty containers of Elmer’s glue and glue sticks. Students and teachers rinse out the bottles, which are then sent to Wal-Mart for recycling. Find out more at elmersgluecrew.com.

Glue strips and inserts in magazines: Lotion samples and nonpaper promotional items affixed to glue strips in magazines should be removed because they can jam up recycling equipment (scented perfume strips, on the other hand, are fine). “One of the biggest challenges we get is pages of promotional stickers and stamps,” says Matsch, “which can adhere to the machinery and tear yards of new paper fiber.”

H

Hangers (plastic): These are not widely accepted at recycling centers, because there aren’t enough of them coming through to make it worthwhile. However, some cities, such as Los Angeles, are equipped to recycle them. You might consider donating them to a thrift store.

Hangers (wire): Some dry cleaners and Laundromats will reuse them. Otherwise, they can be recycled with other household metals. But be sure to remove any attached paper or cardboard first.

Hearing aids: The Starkey Hearing Foundation (starkeyhearingfoundation.org) recycles used hearing aids, any make or model, no matter how old. Lions Clubs also accept hearing aids (as well as eyeglasses) for reuse; log on to donateglasses.org to find designated collection centers near you.

Holiday cards: After they’ve lined your mantel for two months, you could throw them into the recycling bin, or you could give them a whole new life. St. Jude’s Ranch for Children (stjudesranch.org), a nonprofit home for abused and neglected youths, runs a holiday-card reuse program in which the kids cut off the front covers, glue them onto new cards, and sell the result―earning them money and confidence.

I

iPods: Bring in an old iPod to an Apple store and get 10 percent off a new one. Your out-of-date iPod will be broken down and properly disposed of. The catch? The discount is valid only that day, so be prepared to buy your new iPod.

J

Jam jars: Wherever there is container-glass recycling (meaning glass jars and bottles), jam jars are eligible. It helps if you remove any remaining jam, but no need to get obsessive―they don’t have to be squeaky clean. Before putting them in the bin, remove their metal lids and recycle those with other metals.

Juice bags: Because most are a combination of a plastic polymer and aluminum, these are not recyclable. But TerraCycle will donate 2 cents for each Honest Kids, Capri Sun, and Kool-Aid Drink pouch and 1 cent for any other brand you collect and send in to the charity of your choice. The organization provides free shipping, too. What does TerraCycle do with all those pouches? Turns them into colorful purses, totes, and pencil cases that are sold at Target and Walgreens stores throughout the country. To get started, go to terracycle.net.

K

Keys and nail clippers: For many recycling centers, any metal that isn’t a can is considered scrap metal and can be recycled. “There’s not a whole lot of scrap metal we wouldn’t take,” says Kite. “It’s a huge market now.”

L

Leather accessories: If your leather goods are more than gently worn, take them to be fixed. If they’re beyond repair, they have to be thrown in the trash―there’s no recycling option. (A product labeled “recycled leather” is often made from scraps left over from the manufacturing process, which is technically considered recycling.) Donate shoes in decent condition to solesforsouls.org, a nonprofit that collects used footwear and distributes it to needy communities.

M

Makeup: Makeup can expire and is none too pretty for the earth when you throw it in the trash (chemicals abound in most makeup). Some manufacturers are making progress on this front. People who turn in six or more empty MAC containers, for example, will receive a free lipstick from the company in return; SpaRitual nail polishes come in reusable, recyclable glass; and Josie Maran Cosmetics sells biodegradable plastic compacts made with a corn-based resin―just remove the mirror and put the case in your compost heap.

Mattresses and box springs: Mattresses are made of recyclable materials, such as wire, paper, and cloth, but not all cities accept them for recycling. (Go to earth911.org to find out if yours does.)

Metal flatware: If it’s time to retire your old forks, knives, and spoons, you can usually recycle them with other scrap metal.

Milk cartons with plastic spouts and caps: Take off and throw away the cap (don’t worry about the spout―it will be filtered out during the recycling process). As for the carton, check your local recycling rules to see whether you should toss it with plastics and metals or with paper.

Mirrors: These aren’t recyclable through most municipal recyclers, because the chemicals on the glass can’t be mixed with glass bottles and jars. You can donate them to secondhand stores, of course. Or if the mirror is broken, put it in a paper bag for the safety of your trash collectors. To find out what your municipality recycles, call 800-CLEANUP or visit recyclingcenters.org.

N

Nikes and other sneakers: Nike’s Reuse-a-Shoe program (nikereuseashoe.com) accepts old sneakers (any brand) and recycles them into courts for various sports so kids around the world have a place to play. You can drop them off at a Nike store, other participating retailers, athletic clubs, and schools around the country (check the website for locations), or mail them to Nike Recycling Center, c/o Reuse-a-Shoe, 26755 SW 95th Avenue, Wilsonville OR 97070. If your sneakers are still in reasonable shape, donate them to needy athletes in the United States and around the world through oneworldrunning.com. Mail them to One World Running, P.O. Box 2223, Boulder CO 80306.

Notebooks (spiral): It may seem weird to toss a metal-bound notebook into the paper recycling, but worry not―the machinery will pull out smaller nonpaper items. One caveat: If the cover is plastic, rip that off, says Matsch. “It’s a larger contaminant.”

O

Office envelopes

- Envelopes with plastic windows: Recycle them with regular office paper. The filters will sieve out the plastic, and they’ll even take out the glue strip on the envelope flaps.

- FedEx: Paper FedEx envelopes can be recycled, and there’s no need to pull off the plastic sleeve. FedEx Paks made of Tyvek are also recyclable (see below).

- Goldenrod: Those ubiquitous mustard-colored envelopes are not recyclable, because goldenrod paper (as well as dark or fluorescent paper) is saturated with hard-to-remove dyes. “It’s what we call ‘designing for the dump,’ not the environment,” says Matsch.

- Jiffy Paks: Many Jiffy envelopes―even the paper-padded ones filled with that material resembling dryer lint―are recyclable with other mixed papers, like cereal boxes. The exception: Goldenrod-colored envelopes must be tossed.

- Padded envelopes with Bubble Wrap: These can’t be recycled. The best thing you can do is reuse them.

- Tyvek: DuPont, the maker of Tyvek, takes these envelopes back and recycles them into plastic lumber. Turn one envelope inside out and stuff others inside it. Mail them to Tyvek Recycle, Attention: Shirley B. Wright, 2400 Elliham Avenue #A, Richmond VA 23237. If you have large quantities (200 to 500), call 866-338-9835 to order a free pouch.

P

Packing materials: Styrofoam peanuts cannot be recycled in most areas, but many packaging stores (like UPS and Mail Boxes Etc.) accept them. To find a peanut reuser near you, go to loosefillpackaging.com. Some towns recycle Styrofoam packing blocks; if yours doesn’t, visit epspackaging.org to find a drop-off location, or mail them in according to the instructions on the site. Packing pillows marked “Fill-Air” can be deflated (poke a hole in them), then mailed to Ameri-Pak, Sealed Air Recycle Center, 477 South Woods Drive, Fountain Inn SC 29644. They will be recycled into things like trash bags and automotive parts.

Paint: Some cities have paint-recycling programs, in which your old paint is taken to a company that turns it into new paint. Go to earth911.org to see if a program exists in your area.

Pendaflex folders: Place these filing-cabinet workhorses in the paper bin. But first cut off the metal rods and recycle them as scrap metal.

Phone books: Many cities offer collection services. Also check yellowpages.com/recycle, or call AT&T’s phone book–recycling line at 800-953-4400.

Pizza boxes: If cheese and grease are stuck to the box, rip out the affected areas and recycle the rest as corrugated cardboard. Food residue can ruin a whole batch of paper if it is left to sit in the recycling facility and begins to decompose.

Plastic bottle caps: Toss them. “They’re made from a plastic that melts at a different rate than the bottles, and they degrade the quality of the plastic if they get mixed in,” says Kite.

Plastic wrap (used): Most communities don’t accept this for recycling because the cost of decontaminating it isn’t worth the effort.

Post-its: The sticky stuff gets filtered out, so these office standbys can usually be recycled with paper.

Prescription drugs: The Starfish Project (thestarfish-project.org) collects some unused medications (TB medicines, antifungals, antivirals) and gives them to clinics in Nigeria. The organization will send you a prepaid FedEx label, too.

Printer-ink cartridges: Seventy percent are thrown into landfills, where it will take 450 years for them to decompose. “Cartridges are like gas tanks,” says Jim Cannan, cartridge-collection manager at Recycleplace.com. “They don’t break. They just run out of ink. Making new ones is like changing motors every time you run out of gas.” Take them to Staples and get $3 off your next cartridge purchase, or mail HP-brand cartridges back to HP.

Q

Quiche pans and other cookware: These can be put with scrap metal, and “a plastic handle isn’t a problem,” says Tom Outerbridge, manager of municipal recycling at Sims Metal Management, in New York City.

R

Recreational equipment: Don’t send tennis rackets to your local recycling center. “People may think we’re going to give them to Goodwill,” says Sadonna Cody, director of government affairs for the Northbay Corporation and Redwood Empire Disposal, in Santa Rosa, California, “but they’ll just be trashed.” Trade sports gear in at Play It Again Sports (playitagainsports.com), or donate it to sportsgift.org, which gives gently used equipment to needy kids around the world. Mail to Sports Gift, 32545 B Golden Lantern #478, Dana Point CA 92629. As for skis, send them to skichair.com, 4 Abbott Place, Millbury MA 01527; they’ll be turned into Adirondack-style beach chairs.

Rugs (cotton or wool): If your town’s recycling center accepts rugs, great. If not, you’re out of luck, because you can’t ship rugs directly to a fabric recycler; they need to be sent in bulk. Your best bet is to donate them to the thrift store of a charity, like the Salvation Army.

S

Shopping bags (paper): Even those with metal grommets and ribbon handles can usually be recycled with other paper.

Shopping bags (plastic): If your town doesn’t recycle plastic, you may be able to drop them off at your local grocery store. Safeway, for example, accepts grocery and dry-cleaning bags and turns them into plastic lumber. (To find other stores, go to plasticbagrecycling.org.) What’s more, a range of retailers, like City Hardware, have begun to use biodegradable bags made of corn. (BioBags break down in compost heaps in 10 to 45 days.)

Shower curtains and liners: Most facilities do not recycle these because they’re made of PVC. (If PVC gets in with other plastics, it can compromise the chemical makeup of the recycled material.)

Six-pack rings: See if your local school participates in the Ring Leader Recycling Program (ringleader.com); kids collect six-pack rings to be recycled into other plastic items, including plastic lumber and plastic shipping pallets.

Smoke detectors: Some towns accept those that have beeped their last beep. If yours doesn’t, try the manufacturer. First Alert takes back detectors (you pay for shipping); call 800-323-9005 for information.

Soap dispensers (pump): Most plastic ones are recyclable; toss them in with the other plastics.

Stereos and VCRs: Visit earth911.org for a list of recyclers, retail stores, and manufacturers near you that accept electronics. Small companies are popping up to handle electronic waste (or e-waste) as well: Greencitizen.com in San Francisco will pull apart your electronics and recycle them at a cost ranging from nothing to 50 cents a pound. And the 10 nationwide locations of freegeek.org offer a similar service.

T

Takeout-food containers: Most are not recyclable. Paper ones (like Chinese-food containers) aren’t accepted because remnants can contaminate the paper bale at the mill. Plastic versions (like those at the salad bar) are a no-go too.

Tinfoil: It’s aluminum, not tin. So rinse it off, wad it up, and toss it in with the beer and soda cans.

Tires: You can often leave old tires with the dealer when you buy new ones (just check that they’ll be recycled). Worn-out tires can be reused as highway paving, doormats, hoses, shoe soles, and more.

Tissue boxes with plastic dispensers: The plastic portion will be filtered out during the recycling process, so you can usually recycle tissue boxes with cardboard.

Toothbrushes: They’re not recyclable, but if you buy certain brands, you can save on waste. Eco-Dent’s Terradent models and Radius Source’s toothbrushes have replaceable heads; once the bristles have worn out, snap on a new one.

Toothpaste tubes: Even with all that sticky paste inside, you can recycle aluminum tubes (put them with the aluminum cans), but not plastic ones.

TVs: Best Buy will remove and recycle a set when it delivers a new one. Or bring old ones to Office Depot to be recycled. Got a Sony TV? Take it to a drop-off center listed at sony.com/recycle.

U

Umbrellas: If it’s a broken metal one, drop the metal skeleton in with scrap metal (remove the fabric and the handle first). Plastic ones aren’t accepted.

Used clothing: Some towns recycle clothing into seat stuffing, upholstery, or insulation. Also consider donating clothing to animal boarders and shelters, where it can be turned into pet bedding.

Utensils (plastic): “There is no program in the country recycling plastic flatware as far as I know,” says Matsch. “The package might even say ‘recyclable,’ but that doesn’t mean much.”

V

Videotapes, cassettes, and floppy disks: These aren’t accepted. “Videotapes are a nightmare,” says Outerbridge. “They get tangled and caught on everything.” Instead, send tapes to the ACT (actrecycling.org) facility in Columbia, Missouri, which employs disabled people to clean, erase, and resell videotapes. You can also send videotapes, cassettes, and floppy disks to greendisk.com; recycling 20 pounds or less costs $6.95, plus shipping.

W

Wheelchairs: Go to lifenets.org/wheelchair, which acts as a matchmaker, uniting wheelchairs with those who need them.

Wine corks: To turn them into flooring and wall tiles, send them to Wine Cork Recycling, Yemm & Hart Ltd., 610 South Chamber Drive, Fredericktown MO 63645. Or put them in a compost bin. “They’re natural,” says Matsch, “so they’re biodegradable.” Plastic corks can’t be composted or recycled.

Wipes and sponges: These can’t be recycled. But sea sponges and natural sponges made from vegetable cellulose are biodegradable and can be tossed into a compost heap.

Writing implements: You can’t recycle pens, pencils, and markers, but you can donate usable ones to schools that are short on these supplies. At iloveschools.com, teachers from around the United States specify their wish lists. And there’s always the option of buying refillable pencils and biodegradable pens made of corn (like those at grassrootsstore.com) so that less waste winds up in the landfill.

X

Xmas lights: Ship your old lights to holidayleds.com, Attention: Recycling Program, 120 W. Michigan Avenue, Suite 1403, Jackson MI 49201. The company will send you a coupon for 10 percent off its LED lights, which use 80 percent less energy and last 10 years or more. And they’re safer, too. LEDs don’t generate much heat, whereas incandescents give off heat, which can cause a dry Christmas tree to catch fire.

Y

Yogurt cups: Many towns don’t recycle these because they’re made of a plastic that can’t be processed with other plastics. But Stonyfield Farm has launched a program that turns its cups into toothbrushes, razors, and other products. Mail to Stonyfield Farm, 10 Burton Drive, Londonderry NH 03053. Or you can join TerraCycle’s Yogurt Brigade (terracycle.net) to recycle Stonyfield containers and raise money for your favorite charity. For every cup collected, Stonyfield will donate 2 cents or 5 cents, depending on the cup size.

Z

Zippered plastic bags: Venues that recycle plastic bags will also accept these items, as long as they are clean, dry, and the zip part has been snipped off (it’s a different type of plastic).

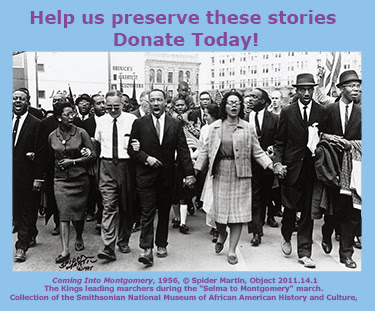

So, today is Cinco de Mayo; the history behind why Americans celebrate May 5th had me thinking about how a small group of people definitely living in a different era took a stand and while there are many stories of how people in our past stood up; such as John Lewis, MLK,Dorothy Height and others , who most often marched … Peacefully — maybe we in the 21st Century should gain strength from these stories of how these great people stood up f themselves, had the courage to challenge laws rules and legislation that clearly perpetuated discriminatory behavior …

So, today is Cinco de Mayo; the history behind why Americans celebrate May 5th had me thinking about how a small group of people definitely living in a different era took a stand and while there are many stories of how people in our past stood up; such as John Lewis, MLK,Dorothy Height and others , who most often marched … Peacefully — maybe we in the 21st Century should gain strength from these stories of how these great people stood up f themselves, had the courage to challenge laws rules and legislation that clearly perpetuated discriminatory behavior …

You must be logged in to post a comment.