1. A smaller cost-of-living adjustment

Each year, Social Security recipients are entitled to a cost-of-living adjustment or COLA.

This serves as a raise for Social Security beneficiaries, many of whom rely on their monthly checks as their primary source of income.

The purpose of COLAs is to allow seniors to retain their buying power in the face of inflation (rising prices of goods and services)

However, due to low inflation in recent years, COLAs increases have been very small.

For example, in 2020, the COLA increase was 1.6%.

Social Security benefits will see a Cost of Living Adjustment of 1.3% in 2021. On Average, that equals an additional $20 a month.

This will increase the average Social Security retirement benefits check from $1,523 to $1,543.

Many retirees won’t see the impact of this increase in their pockets, however.

That’s because this $20 a month increase will likely be offset in part by higher Medicare premiums and deductibles in 2021.

For reference, here are the COLA increases over the last 10 years:

Social Security COLA History

Here’s a look at COLA increases since 2011.

2020: 1.6%

2019: 2.8%

2018: 2%

2017: 0.3%

2016: No increase.

2015: 1.7%

2014: 1.5%

2013: 1.7%

2012: 1.7%

2011: 3.6%

As you can see, the COLA increases have been stingy, especially when one considers the rising cost of healthcare, including Medicare.

Medicare costs to rise

Medicare cost increases are one of the biggest financial burdens on seniors. 2021 will be no different.

Here’s how much Medicare costs will increase in 2021:

- The standard monthly premium for Medicare Part B will be $148.50, up from $144.60 in 2020.

- The annual deductible for Medicare Part B will be $203 — a $5 increase.

- The Medicare Part A inpatient hospital deductible will be $1,484 — a $76 increase.

2. The earnings limit for working retirees will go up

If you claim Social Security retirement benefits before reaching your full retirement age (FRA) and also continue working, continue reading.

As you are probably aware, the Social Security Administration will withhold some of your benefits if your income exceeds “the earnings limit”.

In 2021, the Social Security earnings limit increases to the following:

- From $18,240 to $18,960 if you will reach full retirement age after 2021

- From $48,600 to $50,520 if you will reach full retirement age in 2021

- No limit on earnings if you are full retirement age or older for the entire year.

3. Earnings subject to Social Security tax will increase

The maximum amount of a worker’s income that is subject to Social Security payroll taxes will rise from $137,700 in 2020 to $142,800 in 2021.

That means that you will pay Social Security taxes on any income you make up $142,800 in 2021.

However, any additional income you earn beyond the $142,800 will not be subject to Social Security payroll taxes.

Remember that there is no earnings limit on Medicare taxes.

This means every dollar of earned income is subject to Medicare tax.

Finally, the Social Security payroll tax rate will remain the same in 2021.

This means employees pay 6.2% and employers pay another 6.2%, for a total of 12.4% for the self-employed.

Self-employed individuals pay the entire 12.4% in Social Security taxes.

4. Lifetime work credits Amount Go Up

How much you have to earn per quarter to qualify for Social Security retirement benefits will go up.

To receive Social Security retirement benefits, most people need to accumulate at least 40 ‘credits’ during their working lifetime.

Currently, you can earn up to four credits per year if you work and pay Social Security taxes.

In 2021, the minimum about you have to earn a year to get the four credits for that year was $1470, an increase of $60 from 2020.

5. The Full Retirement Age will go up

As has been happening in recent years, the Full Retirement Age (FRA) for Social Security benefits is going up again.

In 2021, the full retirement age going higher by two months, to 66 years and 10 months for those born in 1959.

The full retirement age is the age when you are entitled to 100 percent of your Social Security benefits.

If you were born between 1943 and 1954, your full retirement age is 66.

However, if you were born in 1955, it is 66 and 2 months.

For those born between 1956 and 1959, it gradually increases, and for those born in 1960 or later, it is 67.

The earliest a recipient can start collecting Social Security retirement benefits is age 62.

It is important to note that seniors who claim Social Security before their full retirement age receive reduced payments.

For example, if you turn 62 and start receiving Social Security benefits in 2021, your monthly benefits will be 29.17% less than you will receive at your FRA.

socialsecurityportal.com

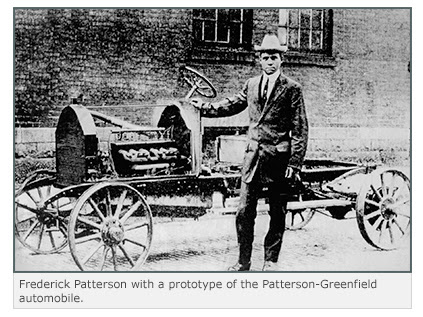

At first, the company offered repair and restoration services for the “horseless carriages” that were beginning to proliferate on the streets of Greenfield. No doubt this gave workers the opportunity to gain some hands-on knowledge about these noisy, smoky and often unreliable contraptions. Like his father, Frederick was a strong believer in advertising and placed his first ad for auto repair services in the local paper in 1913. Initially, the work mostly involved repainting bodies and reupholstering interiors, but as the shop gained more experience with engines and drivetrains, they began to offer sophisticated upgrades and improvements to electrical and mechanical systems as well.

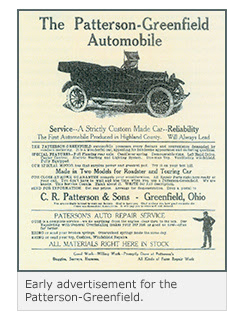

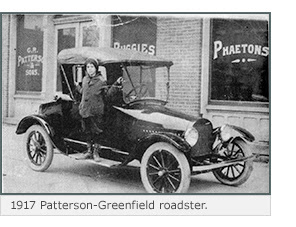

At first, the company offered repair and restoration services for the “horseless carriages” that were beginning to proliferate on the streets of Greenfield. No doubt this gave workers the opportunity to gain some hands-on knowledge about these noisy, smoky and often unreliable contraptions. Like his father, Frederick was a strong believer in advertising and placed his first ad for auto repair services in the local paper in 1913. Initially, the work mostly involved repainting bodies and reupholstering interiors, but as the shop gained more experience with engines and drivetrains, they began to offer sophisticated upgrades and improvements to electrical and mechanical systems as well. Orders began to come in, and C.R. Patterson & Sons officially entered the ranks of American auto manufacturers. Over the years, several models of coupes and sedans were offered, including a stylish “Red Devil” speedster. Ads featured the car’s 30hp Continental 4-cylinder engine, full floating rear axle, cantilever springs, electric starting and lighting, and a split windshield for ventilation. The build quality of the Patterson-Greenfield automobile was as highly regarded as it had been with their carriages.

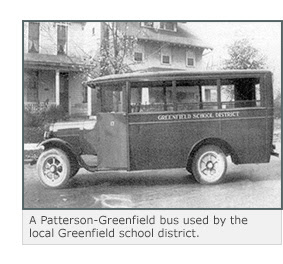

Orders began to come in, and C.R. Patterson & Sons officially entered the ranks of American auto manufacturers. Over the years, several models of coupes and sedans were offered, including a stylish “Red Devil” speedster. Ads featured the car’s 30hp Continental 4-cylinder engine, full floating rear axle, cantilever springs, electric starting and lighting, and a split windshield for ventilation. The build quality of the Patterson-Greenfield automobile was as highly regarded as it had been with their carriages. In 1918, having built by some estimates between 30 and 150 vehicles, C.R. Patterson & Sons halted auto production and concentrated once again on the repair side of the business. But they weren’t done yet. In the 1920s, the company began building truck and bus bodies to be fitted on chassis made by other manufacturers. It was in a sense a return to their original skills in building carriage bodies without engines and drivetrains and, for a period of time, the company was quite profitable. Then in 1929, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression set in. As with many small businesses, sales dried up and loans were hard to obtain. The company, now run by the sons of Frederick Patterson, soldiered on until 1939 when, after 74 years, C.R. Patterson & Sons closed its doors forever.

In 1918, having built by some estimates between 30 and 150 vehicles, C.R. Patterson & Sons halted auto production and concentrated once again on the repair side of the business. But they weren’t done yet. In the 1920s, the company began building truck and bus bodies to be fitted on chassis made by other manufacturers. It was in a sense a return to their original skills in building carriage bodies without engines and drivetrains and, for a period of time, the company was quite profitable. Then in 1929, the stock market crashed and the Great Depression set in. As with many small businesses, sales dried up and loans were hard to obtain. The company, now run by the sons of Frederick Patterson, soldiered on until 1939 when, after 74 years, C.R. Patterson & Sons closed its doors forever.

You must be logged in to post a comment.